I ask you this through that same Jesus Christ Our Lord, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit as one God, now and for ages of ages. Amen.

Tuesday, August 30, 2005

Prayer for New Orleans and all Katrina victims

I ask you this through that same Jesus Christ Our Lord, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit as one God, now and for ages of ages. Amen.

Another thing to like about B16...

And I don't mean the vitamin, which I also acknowledge as a Good Thing.

And I don't mean the vitamin, which I also acknowledge as a Good Thing.Apparently, the Pope met secretly last Saturday with Oriana Fallaci, the acerbic Italian author who most recently ran afoul of a court in her country for her highly critical book about Islam's relations with the West. She faces a warrant for her arrest on a hate-crime indictment, which is why she now spends most of her time in New York. Having read the book, I would say that the charge is absurd because, even though it is arguably merited under the applicable law, that law is so broad that its application in a case such as this is a violation of basic human rights. It is probably because the Italian Government is sensitive to such criticism that, even though they doubtless knew of her arrival in Italy, Fallaci was not arrested at the airport. Deference to the Pope probably had something to do with that as well. Kudos all around!

Of course I don't know what was said in that meeting, and probably no more than a handful of people other than Fallaci and Benedict do. But I'm certain the meeting shows at least two things: the Pope's pastoral solicitude for a baptized Catholic whom, even though she now professes atheism, he still considers part of his flock; and his willingness to seek input from people who have no particular Catholic axe to grind. He's evinced the latter with some professional philosophers too; but the problem of Islamic jihadism is very concrete and serious in the world today, and the Pope's remarks during World Youth Day(s) indicate that he is thinking about it with unflinching realism. As if his past didn't prove as much already, this is not a man who shies away from the hard issues just because they are controversial.

As I've said before elsewhere, B16 seems to be just the vitamin for the Church now.

Monday, August 29, 2005

The struggle continues...

Thanks.

Sunday, August 28, 2005

The rumblings: will there be a quake?

The spin in such words as 'tarnish' and 'soften' is plain as a pikestaff. If the envisioned policy is adopted, it would amount to no more than a pastoral attempt to address two major problems, one of which is known to all the world and one of which is undeniable once one thinks about it. The more widely known problem is that the majority of minors sexually abused by Catholic priests are (or were, since most cases are fairly old) adolescent boys; the other problem is that homosexuals in the seminary live in close quarters with other men, some of whom are gay themselves and some of whom, gay or not, must pose a temptation. A new policy of keeping homosexuals out of the seminary would go a long way toward solving both problems. Is that so objectionable in itself? I am far from alone in thinking it is not. But what we hear so far is that announcing such a policy would spoil the Pope's PR efforts, as if that is what he and his advisors are mainly worried about. Since it's taken for granted that that is what every public figure is supposed to be most worried about, it does not occur to the writer that the Pope might have bigger fish to fry—like reducing the amount of sodomy on boys and preventing the perpetuation of homosexual cliques among priests.

And that points up the unintended irony in all this. For perfectly understandable reasons, nothing has provoked greater contempt for the Catholic Church in the last several years than the sexual abuse of minors by priests. Yet "progressives" never, ever say that part of the solution might to keep homosexuals, a good number of whom fancy adolescent boys, from entering the seminary—where they could and do fancy each other—or keep them from being ordained—a status that makes their pickings far wider. That would be so intolerant, so unenlightened, so "homophobic." No, their prescription is the same one they've been peddling since Vatican II—ordain women and married men too, thus making gender and marital status as well as sexual orientation irrelevant as criteria for ordination. The idea seems to be that, if the pool is dirty, you just add more water rather than remove the contaminants. We know how well that works. Is there any evidence that the clergy of the Episcopal Church in the U.S. and Canada, which includes women and married men as well as avowedly active homosexuals, is in better shape morally than the Catholic priesthood? Given the slope built by media bias, one has to labor uphill to learn that the answer is actually no.

To compound the irony, the very policy being contemplated and feared was actually adopted by the widely beloved Pope John XXIII in 1961! It has never been rescinded, but neither have most bishops paid it any notice. Some traditionalist Catholics, embittered by much that has taken place in the Church during the intervening years, blame John XXIII himself for such negligence. Whatever one may think of his policy of keeping the sins of priests as private as possible, largely by utilizing the seal of the confessional, there can be no doubt that one of its effects was to render his ban on homosexual seminarians a dead letter. But of course, some such sins have long been felonies under secular law and have recently been prosecuted as such in criminal courts. Now that they've occasioned huge civil-damage awards as well, the Church can literally no longer afford to avoid owning and attacking the deepest root of the problem. But the progressives are outraged by the very idea that said root is anything other than the tendency of bishops to dodge accountability and "openness." Thus if they had their way, the Church would remain permanently between a rock and a hard place.

For those who understand why, no explanation of that is necessary; for those who do not, no explanation is possible. The only objection I find worth considering is that renewing John XXIII's ban would substantially reduce the pool of candidates for the seminary. No doubt it would, at least in the short term; but it is at least arguable that such a pruning would facilitate new growth in the long term. My only fear is that the bishops, who seem collectively incapable of radical reform without Roman intervention, would find yet another way to make the ban a dead letter. It wouldn't be so hard: just take a man's word for it that he isn't gay. Lying to get what one wants is human nature, after all. Accommodating that wouldn't be good enough in today's climate; but refusing to accommodate it might expose the bishops to more bad PR than most seem to have the belly to handle.

So I say to Benedict: bring it on!

The single "vocation"

I agree that much hinges here on definition. I propose the following.

The baptismal vocation is to die and rise in Christ, thus being incorporated into his Body and being given eternal life. Thus Christians all "called" out of darkness into His marvelous light. Living out such a vocation can, however, take many specific forms that are also called vocations.Those in consecrated life are "called" to bind themselves to Christ in a more explicitly visible form that most believers. Clergy and religious are thus meant to represent for the Church what the Church as a whole is meant to represent for the world. Those in married life are also "called" to bind themselves to Christ by making an irrevocable gift of themselves to a particular person. Sacramental marriage thus signifies, and helps to make concrete, the relationship between Christ and his Church. That is not as explciit a sign of Christ as the consecrated state because, outwardly and visibly, it is not as different from what unbelievers do. Hence the term 'vocation' has often been used for consecrated life as opposed to marriage: the consecrated are called out of the ordinary course, i.e. marriage, to something more visibly and objectively Christlike.

Both consecrated and married life are "avowed" forms of vocation: they are constituted by specific promises. As such, they are recognizable forms of the baptismal vocation. By contrast, those who are called to neither consecrated nor married life have total flexibility in answering the baptismal vocation. There are no "vows" specifying for them what form the answer is to take. So we might define the "single" vocation as simply the Christian vocation unspecified by vows.

"You have duped me, Lord..."

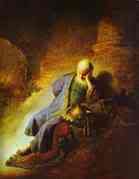

So reads Jeremiah 20:7, from the readings at Mass celebrated in the normative rite of the Latin Church today. Indeed the entire reading from Jeremiah today is one of my favorites from the Bible; I like to meditate on it in conjunction with Isaiah 55: 6-11, which is my absolute favorite reading from the Bible. But today I want to focus on a central theme of the Mass readings.

So reads Jeremiah 20:7, from the readings at Mass celebrated in the normative rite of the Latin Church today. Indeed the entire reading from Jeremiah today is one of my favorites from the Bible; I like to meditate on it in conjunction with Isaiah 55: 6-11, which is my absolute favorite reading from the Bible. But today I want to focus on a central theme of the Mass readings.Jeremiah and the Apostle Peter (see today's Gospel reading, linked above) had in common an initial, and of course quite natural, inability to understand or appreciate the importance of suffering in the spiritual life. In that respect, they represent all of us. We abhor suffering and thus tend to flee it; if we didn't, it wouldn't be suffering. Jeremiah's prophetic words, which he knew were from God and felt compelled to proclaim, earned him fierce opposition and derision; according to rabbinical tradition, he was eventually murdered by his countrymen in Egypt, where he had taken refuge from the conquest and razing of Jerusalem by King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. But well before that he had to struggle not to become bitterly cynical about the God he obeyed. He didn't quite get the point of being rewarded for his fidelity with as much misery as he predicted, correctly, his fellow Jews would get for their infidelity. But he apparently never lost the conviction that there was a point.

Peter didn't get it either in the case of his beloved friend and master, Jesus of Nazareth. Naturally, Peter want Jesus to triumph as the king he was by right rather than be killed as a public nuisance. Peter didn't understand until after the Ascension what is now a flip truism: "No cross, no crown"—or, to put it in debased secular form: "No pain, no gain." No more than Jeremiah did he appreciate the ironic sense of humor shown by a God who saved his people, indeed the whole world, by getting himself tortured and executed by them and thus taking the punishment that was theirs.

But of course the logic of the thing is unassailable once the premises come from God not man. As Jesus said: For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it,but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. Why? Our life in this vale of tears is fatally flawed by original and actual sin; clinging to it—i.e., living "in the flesh" rather than "in the spirit"—implicates us hopelessly in the spiritual death that caused physical death to enter the world. To enjoy the life God has planned for us from all eternity, we must accept suffering as the negation of what is fatally flawed about ourselves. That is what teaches us the detachment necessary for dying to self in order to live for God. The seed must "fall to the ground and die" before it can bear lasting fruit.

Such, in effect, is St. Paul's advice in today's second reading:

I urge you, brothers and sisters, by the mercies of God, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God, your spiritual worship. Do not conform yourselves to this age but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and pleasing and perfect.

The "renewal" of our minds Paul urges is a radical re-orientation, entailed by repentance and conversion, about suffering. Our supreme rule of living is no longer to be the pleasure principle but rather the high priesthood of Christ, who is as much victim as priest and is priest precisely because he has been victim. That is the pattern to be emulated by all the baptized, who form the Mystical Body of Christ. That is what the "priesthood of believers" consists in. It is not an opportunity to wield authority in the Church, though a few are granted that privilege and should accordingly tremble. It is an opportunity to become like Christ in the large and small matters of everyday life.

An attitude like that doesn't come naturally; it is a supernatural gift that must be gratefully accepted and earnesty cultivated. Most of us fail often to do so; I know I do. But I pray for the help to get up and resume the renewal of my mind; the more God grants that prayer, the more abject my failures seem, both large and small; yet the more glorious the real potential for growth also seems. Each of us knows how to enter into that pattern if we're willing to listen to the Holy Spirit. Like many men in this world, I find that my job helps.

The work is the pain; the paycheck is the gain; and even a substantial portion of the latter goes, directly or indirectly, not for my own gratification but for the needs of others to whom it is due as simple justice. All that is normal and apparently unremarkable. But I wouldn't be able to get through a day without remembering that it is a very important way in which I exercise my priesthood. Each in their own fashion, everybody has the opportunity to die and thus live. Suffering is unavoidable; we can either use it well or bring more of it on ourselves by our refusal to use it well.

For the sake of finding our true lives and homes, we must take the opportunity early and often.

Saturday, August 27, 2005

A fresh perspective on Catholic singles

I especially like the distinction between the "avowed" state, whether in the form of marriage or consecrated life, and the charism of freedom that characterizes the state of those who are called to singlehood.

Part V comes next week.

Friday, August 26, 2005

The borderline between spirit and psyche

I have encountered some mental-health professionals who, despite their training and official professional doctrine, definitely do apply the categories of good and evil. I shall leave aside the debate about homosexuality, which in the present state of things is more about competing ideologies than scientific fact. But depressed people, narcissists, and multiple-personality sufferers, among others, are sometimes held morally accountable for their condition. Sometimes such people are held accountable for letting themselves get into such a state; other times, they are held accountable for continuing to be in such a state. When it's both, we have full-blown moral judgment. Even granted Jesus Christ's wise injunction "not to judge"—i.e., not to claim knowledge that only God can have—such a judgment is doubtless objectively true in some cases; in others, it doubtless is not. But the mere fact that it naturally suggests itself puts the lie to the widespread claim that the conditions for which people are sometimes judged are just mental illnesses. Such "illnesses"—sometimes in their origin, sometimes in their persistence—can themselves be symptoms of evil choices made in the heart, ones that could have been otherwise.

I do not suggest that we deal with such persons merely as "sinners" rather than as "patients." We know too much about brain chemistry and other influences to dispense with treatment in the familiar sense. But it seems reasonable that, if people must want to get well in order to get well, then obversely, something evil that they want accounts for their getting or staying sick.

M. Scott Peck, of The Road Less Traveled fame, has had some interesting thoughts on this. He does not pretend to have an all-encompassing theory, and of course neither do I. But one thing I'm sure of: Satan, who is real and personal, is especially active among the mentally ill.

Monday, August 22, 2005

The Infallibility of the Ordinary Magisterium

The far better-known dogma of papal infallibility, formally defined by Vatican I, concerns the exercise not of the ordinary but of the "extraordinary" magisterium, of which it is also an instance. The ordinary magisterium is simply the teaching authority of the Church as exercised in ordinary, day-to-day circumstances. The extraordinary magisterium is the teaching authority of the Church as exercised in special circumstances calling either for resolution of a disputed question or clarification of traditional doctrine in more precise and authoritative terms; almost always, that occurs by means of the decrees of a general council or a unilateral papal definition. The ordinary magisterium proposes for our belief the entire deposit of faith entrusted to the Church by Jesus Christ himself for preservation and ever-deeper but never-exhaustive understanding; the extraordinary does not add to that deposit, but expresses this or that aspect of it in terms that may never be repudiated even if and when they can be improved. Traditionally, and not terribly controversially, Catholic theologians acknowledge the exercise of the extraordinary magisterium as manifesting the infallibility of the Church as a whole. And in theory at least, most will now grant that the ordinary magisterium can also be exercised infallibly by the bishops as a whole, with or without formal papal confirmation. Thus Lumen Gentium:

Although the individual bishops do not enjoy the prerogative of infallibility, they nevertheless proclaim Christ's doctrine infallibly whenever, even though dispersed through the world, but still maintaining the bond of communion among themselves and with the successor of Peter, and authentically teaching matters of faith and morals, they are in agreement on one position as definitively to be held [definitive tendendam].(40*) This is even more clearly verified when, gathered together in an ecumenical council, they are teachers and judges of faith and morals for the universal Church, whose definitions must be adhered to with the submission of faith.(41*)

Prima facie, one might think that that passage obscures our issue somewhat. The last sentence refers to the extraordinary magisterium even as the former refers to the ordinary; after all, the intent of the bishops in council was to teach about their own infallibility, whether teaching ordinarily or extraordinarily; and whether the quoted teaching is itself "ordinary" or "extraordinary" is itself a matter of debate among theologians. But whoever has the better of that debate, the teaching in question binds Catholics and actually illuminates an important similarity, beyond just its exercise by bishops, between the ordinary and extraordinary magisterium of the bishops.

Whether the infallible exercise of the magisterium described in the quotation be of the ordinary or the extraordinary kind, it entails the bishops' collectively proposing something for belief "definitively." That was a real and vital clarification. It means that infallible exercises of teaching authority need not consist in either the pope's unilaterally or the bishops' collectively propounding formal dogmatic definitions. Something short of that sometimes suffices, in theory at least, for definitiveness and thus infallibility. That puts the lie to the claim, common even among educated Catholics, that only formal dogmatic definitions by popes or by councils ratified by popes require from Catholics "the assent of faith." (The scope of that "religious assent" for which Vatican II called is a separate matter that should be discussed, but which space prevents me from discussing here and now.) What remains controversial, however, is the question by what criteria instances of IOM may be identified. More briefly: just how do we know what is definitive tendendam, short of dogmatic definition?

To a certain extent, the answer seems clear enough. Thus, e.g., in his book Creative Fidelity, whose title is the same as that of a book by Catholic philosopher Gabriel Marcel, ecclesiologist Fr. Francis A. Sullivan argues that the Apostle's Creed, the virginal conception of Jesus, and certain other doctrinal statements fulfill the relevant criteria. Indeed they do; and pointing that out is helpful for appreciating the importance of Vatican II's teaching on IOM. But one may well ask whether sticking to such relatively uncontroversial examples suffices. Given the properly catechetical role of infallibility in general, I don't think it does.

The point of invoking infallibility is to assure the faithful that what is said to be taught infallibly is true. Given as much, of what use is claiming that some person or group is teaching infallibly unless there's some edge to and question about what is being taught? After all, if the bishops each said they were going to die, they would be teaching infallibly but idly. Less trivial but still instructive, Catholics of late have not exactly been in an uproar over the infallible proclamations of the Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Mary. Few Catholics are offended by those dogmas; fewer still dispute them or the claim that they are infallible. Indeed, that is why not a few commentators have said that the dogma of papal infallibility is too radical to risk applying to any but uncontroversial cases and is, for that very reason, all but useless. With IOM too, the cases in which invoking it would be most useful are precisely the most controversial. So is IOM also to be kept under wraps and brought out only when hardly anybody would care?

Some would say so. For a generation after Vatican II, theologians in general and the Vatican in particular said virtually nothing about IOM. (A notable exception is the lengthy article by Germain Grisez and John Ford, "Contraception and the Infallibility of the Ordinary Magisterium," Theological Studies 39, No. 2, June 1978, pp. 258-312.) Such silence was itself notable as debate raged in the Church about the usual issues of sexuality and gender, which remain controversial at least in the mutually reflective eyes of the media and the aging "progressive" wing of Church professionals. But what has gone relatively unnoticed even amid all the controversy is that the previous pope, in concert with the aide of his who is now pope, have actually invoked IOM in at least two cases that can hardly be said to be uncontroversial: women's ordination and abortion.

In his peremptory 1994 "letter" to the bishops on women's ordination, Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, John Paul the Great made the following celebrated (or notorious, depending on one's viewpoint) statement:

Although the teaching that priestly ordination is to be reserved to men alone has been preserved by the constant and universal Tradition of the Church and firmly taught by the Magisterium in its more recent documents, at the present time in some places it is nonetheless considered still open to debate, or the Church's judgment that women are not to be admitted to ordination is considered to have a merely disciplinary force.

Wherefore, in order that all doubt may be removed regarding a matter of great importance, a matter which pertains to the Church's divine constitution itself, in virtue of my ministry of confirming the brethren (cf. Lk 22:32) I declare that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful [emphasis added].

And on October 28, 1995, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith's responsum ad dubium on OS's teaching asserted:

This teaching requires definitive assent, since, founded on the written Word of God, and from the beginning constantly preserved and applied in the Tradition of the Church, it has been set forth infallibly by the ordinary and universal Magisterium (cf. Second Vatican Council, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium 25, 2). Thus, in the present circumstances, the Roman Pontiff, exercising his proper office of confirming the brethren (cf. Lk 22:32), has handed on this same teaching by a formal declaration, explicitly stating what is to be held always, everywhere, and by all, as belonging to the deposit of the faith [emphasis added].

Now of course, the dissenters always point out that Ratzinger's responsum was not an "infallible" statement and therefore cannot be cited to establish that JP2's declaration in OS was itself infallibly made. But that reflex reaction misses the point altogether. It is true that neither document is the sort of document, or utilizes the form of statement, to which Catholics are accustomed as media for infallible teaching; but that is because Catholics traditionally expect, for that purpose, definitions that are acts of the extraordinary magisterium, whereas the two documents were meant to be taken jointly as establishing that the ineligibility of women for priestly ordination has been infallibly taught by the ordinary magisterium. Trying to establish that by means of an act of the papal extraordinary magisterium would accordingly have been self-defeating. Doctrines taught with IOM are, by definition as it were, not defined as dogmas. So if there is such a thing as IOM at all—and there is—then the Magisterium of the Church has to be able to say where it applies without thereby evacuating it. That's just what John Paul and Ratzinger did on the question of women's ordination. An equally impressive, if somewhat less controversial, example of the same sort of move may be found at Evangelium Vitae § 57ff, which I commend to the reader's study.

That such was the previous pope's intent in OS is made abundantly clear by his clause therein: "in order that all doubt may be removed." Doubt was being removed not in the sense of silencing all dissenters but in the sense of establishing, by a definitive act, that IOM here applied. Subjective doubt cannot always be dispelled, but in some cases a teaching can be presented in such a way as to remove all objective grounds for calling it doubtful. The dissenters continue to dissent because some don't believe there is such a thing as IOM at all and others believe that, if there is, it applies only in relatively uncontroversial cases. But as Wojtyla and Ratzinger have also made plain in all the pertinent documents, there are criteria for identifying where IOM applies even in controversial cases: those where the teaching in question "has been preserved by the constant and universal Tradition of the Church and firmly taught by the Magisterium." Such a criterion may dispense with poll-taking or with quibbles about how big the poll's percentage-in-favor must be; a synchronic consensus is not sufficient in itself—as the case of limbo showed—and isn't even necessary if a diachronic consensus ab initio can be identified. Where application of the quoted criterion is controversial even among bishops as well as theologians, the controversy can be settled by an act of the ordinary papal magisterium viewed as itself an indispensable part of that of the bishops as a whole. As Cardinal Dulles has rightly said, the pope can and may "solidify" the relevant consensus "by giving voice to it" in a definitive act that does not define dogma but does indicate what is definitive tendendam.

By such means, OS and EV have helped bring some Catholics into line. That they have not succeeded in doing so for all is only to be expected, for the approach employed is new and based partly on the not-much-older formulation of Vatican II. But that approach has a signal advantage that should be exploited in other controversial cases, such as that of the similarly traditional and unbroken teaching against contraception understood as direct, voluntary interruption of the generative process. By utilizing their magisterium in the way John Paul the Great did, the present and future popes can exercise the Petrine ministry of unity collegially and thus without resurrecting old disputes about the wisdom of unilateral papal definitions of dogma. Surely that is not only of great ecumenical value but also an invitation to Catholics to re-immerse themselves in the riches of their tradition and assimilate more thoroughly to the true mind of the Church. Such is a needed, long-overdue antidote to the left-wing legalism of the progressives that competes with, and has largely supplanted, the right-wing legalism of the traditionalists.

Friday, August 19, 2005

When the basics pack punch

The following from the Pope's first address at World Youth Day is surprisingly basic for such an academician:

"The Ten Commandments are not a burden, but a sign-post showing the path leading to a successful life. This is particularly the case for the young people whom I am meeting in these days and who are so dear to me. My wish is that they may be able to recognize in the Decalogue a lamp for their steps, a light for their path (cf. Ps 119:105). Adults have the responsibility of handing down to young people the torch of hope that God has given to Jews and to Christians, so that “never again” will the forces of evil come to power, and that future generations, with God’s help, may be able to build a more just and peaceful world, in which all people have equal rights and are equally at home."

Basic, but politically subtle. "Equal rights" must be based on the Ten Commandments. How well that resonates with the American Declaration of Independence's reference to "the laws of nature and of nature's God," which specify the "self-evident" truth that "all men are equal" and certain of their right are "unalienable"! So much for secular liberalism. We may and probably should keep church and state separate; but when we thrust God so far out of public life that bedrock moral norms may no longer be acknowledged by the state as anchored in him, then any and all rights are fully reduced to claims that some people not only can but may choose, for reasons of their own, to grant or deny others. There is no middle way. That's a message the EU, and increasingly the US, need to hear. Which will it be?

Following the Decalogue also would help people feel "equally at home." That's why the Pope made such a point of addressing Jews, and the topic of Jewish-Christian relations, as he visited an ancient city in his own homeland. If the German people had truly remembered and cared about the Decalogue, there would have been no Nazi regime and no Shoah. And nowadays there are more nations than the Germans who need to hear the message that all humans equally—the most depraved of malefactors, the innocent in the womb, even the most handicapped—belong in God's world.

There's no better way to get the message heard than to deliver it to young people with the conviction and enthusiasm that can truly touch their hearts. The Pope's full address can be found here.

Tuesday, August 16, 2005

The "theology" of gay marriage: Part Deux

Recently on this blog, I criticized an argument for gay marriage that I found noteworthy because it is theological not secular. Only after composing that post did I discover that its author, Todd Bates, wrote his PhD thesis in philosophy in the same department, and even under the same professor, I did! That it occurs in such a small world makes the debate partly personal for me. As an Episcopalian, of course, Bates does not operate with quite the premises I do as a Catholic; so for me, the rest of his argument's interest has come to lie mostly in how its premises illustrate some of the larger theological problems in the Anglican Communion. Yet now I note a rejoinder to my criticism that defends Bates' argument and comes from a Catholic: Joe Cecil of In Today's News. Hitting at home, that presents something of renewed interest.

Recently on this blog, I criticized an argument for gay marriage that I found noteworthy because it is theological not secular. Only after composing that post did I discover that its author, Todd Bates, wrote his PhD thesis in philosophy in the same department, and even under the same professor, I did! That it occurs in such a small world makes the debate partly personal for me. As an Episcopalian, of course, Bates does not operate with quite the premises I do as a Catholic; so for me, the rest of his argument's interest has come to lie mostly in how its premises illustrate some of the larger theological problems in the Anglican Communion. Yet now I note a rejoinder to my criticism that defends Bates' argument and comes from a Catholic: Joe Cecil of In Today's News. Hitting at home, that presents something of renewed interest.Stated baldly, JC's thesis is that I have failed to show Bates' key premise to be false. I appreciate the implicit acknowledgment that I have in fact identified the key premise; but like another critic of mine to whom I've replied at Pontifications, JC seems to have things precisely backwards. Since the very concept of same-sex marriage is incompatible with the unbroken teaching of the Church, as sustained by Scripture, Tradition, and natural law-arguments, the burden is on the concept's proponents to show that the teaching of the Church is false. That I did not, in my reply to Bates, show that the teaching of the Church is true is no criticism of my claim that Bates failed to show his key premise, which is incompatible with said teaching, to be itself true. Interestingly, Bates has indicated that he is quite circumspect about the potential success of carrying the burden of proof; but JC says some things that can be construed as beginning to do so. So it is to JC's arguments that I shall now briefly address myself.

JC begins his argument with the apparently unexceptionable claim that the author of Ephesians starts with the collective relationship between Christ and the whole Church, and from that relationship, he draws the image of what Christian marriage should be like. (That JC is careful not to identify St. Paul as the author is itself a sign of an education whose premises I would question; but that is an issue for another day.) Thus, the author does not start with the concept of monagamous permanent committed consensual sacramental marriage between persons who possess equal dignity, and draw conclusions from that concept about Christ's relationship to the Church. That much is true. The concept of marriage so understood is distinctively Christian and was not the prevailing social norm in any pre-Christian society. But what is said to follow?

Consider:

He [the author] is drawing from the collective experience of the whole to formulate moral directives for the several or the individual. Interestingly, what the author of Ephesians is doing is saying that Christ is united to the body in such a real way, that this is why Christians cannot divorce: "the two become one flesh."And now the punch line:

...precisely the relationship R between Christ and a man that becomes the basis for a heterosexual man to be mutually submissive to his wife and consider himself in union with her. Thus, if it is the relationship R between Christ and a man that is the basis for a hetersexual man to consider himself in union with his wife, how much more so does R serve as the basis for a homosexual man to consider himself in union with his lover? (Emphasis added.)That is interesting and important. It shows that the Pauline and Christian concept of marriage does indeed depend, to some extent, on how Jesus modelled for men in marriage the kenosis (self-emptying) of which the author of Ephesians, by tradition, also spoke in Philippians 2. The only question is whether gay men can imitate that model just as well in committed homosexual relationships as straight men do in sacramental marriage as traditionally understood by the Church.

The Church's answer is clearly no. In keeping with Paul's very traditional abhorrence of sodomy, unmistakeably expressed elsewhere in his epistles, the Church has always taught that legitimate genital activity must be confined not only to marriage as she has always understood it but also—this is essential—must be of the inherently procreative sort even if, per accidens, procreation happens not to be possible. The ways in which the New Testament and the Church developed the concept of marriage have always assumed that. Accordingly, and following what she understood to be the mind of Christ, the early Church believed that her concept of monogamous, indissoluble, and thus sacramental marriage was simply restoring how things were "in the beginning." From the standpoint of prevailing norms, both Jewish and pagan, marriage so understood was indeed a social innovation; but it was one which was meant to restore what every human society had corrupted, including but not limited to homosexual liaisons. The Church has always insisted—though not always, to be sure, with the same language and emphasis—that the procreative dimension of marital sex must not be separated from the unitive. Somehow the procreative has been understood to be inseparably connected with the unitive as described in Ephesians 5. On such a premise, gay marriage is simply a null hypothesis that, as such, cannot model R as Christ intends.

People nowadays question said insistence largely, I believe, because until very recently it has never been adequately explained. JC, of course, implicitly rejects it, as do almost all "progressive" Catholics. And natural-law explanations, though valid as far as they go, do not go nearly far enough. But a fuller, remarkably profound and beautiful explanation is at hand in John Paul the Great's "theology of the body." It actually explains why the unitive significance of genital activity cannot dispense with the procreative. In so doing, it sublates the old natural-law approach into a richer, higher, more appealing synthesis characterized by a thoroughly biblical personalism. I do not have time or space here to get into the details, but people like JC would do well to explore them before rejecting a premise the Church has always held and is not about to abandon.

In conclusion I note that JC's procedure is, at best, dubiously Catholic. If his position is correct, then the Church has been in error for nearly 2,000 years about a matter of great moral and sacramental importance: the very nature of marriage. Now that consequence by itself would not disturb JC inasmuch as he has elsewhere argued that the Church's refusal to ordain women to the priesthood is "immoral and heretical." (See his post to that effect at Pontifications along with my reply.) But the fact that any person could claim loyalty to a church that he believes has always been in error about at least two matters of great moral and sacramental importance beggars my understanding. That holds quite generally; but in particular I have never understood "progressive" Catholics. If one wants to be progressive in the sort of way JC does, there are mainline Protestant denominations that would make one feel very much at home.

Monday, August 15, 2005

The Feast of the Assumption

As has become their wont, most of the U.S. Catholic bishops are not requiring the faithful to attend Mass today. After all, the Feast of the Assumption of Mary falls on a Monday this year; going to church two days' running is apparently too onerously ascetical for contemporary Americans with cars. And we wonder why there's been a sex scandal among priests? Why the rates of divorce and abortion among Catholics roughly matches that of the general population? I'm no saint either, but that's precisely why I'm going to Mass today. As I age and meditate on the truths of my faith, I am more and more awestruck by the Mother of God and want a little of her to rub off on me. And there's something about this feast which attracts even some secular thinkers.

As has become their wont, most of the U.S. Catholic bishops are not requiring the faithful to attend Mass today. After all, the Feast of the Assumption of Mary falls on a Monday this year; going to church two days' running is apparently too onerously ascetical for contemporary Americans with cars. And we wonder why there's been a sex scandal among priests? Why the rates of divorce and abortion among Catholics roughly matches that of the general population? I'm no saint either, but that's precisely why I'm going to Mass today. As I age and meditate on the truths of my faith, I am more and more awestruck by the Mother of God and want a little of her to rub off on me. And there's something about this feast which attracts even some secular thinkers.The great psychologist Carl Jung, for example, regarded Pope Pius XII's bull Munificentissimus Deus, defining the Assumption as a dogma of the Church, as the most important spiritual event since the Protestant Reformation. Thus:

The logic of the papal declaration cannot be surpassed, and it leaves Protestantism with the odium of being nothing more but a man’s religion which allows no metaphysical representation of woman. In this respect it is similar to Mithraism, and Mithraisim found this prejudice very much to its detriment. Protestantism has obviously not given sufficient attention to the signs of the times which point to the equality of women. But this equality requires to be metaphysically anchored in the figure of "divine" woman, the bride of Christ. Just as the person of Christ cannot be replaced by an organization, so the bride cannot, be replaced by the Church. The feminine, like the masculine, demands an equally personal representation (Answer to Job [Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1954], pp. 170-71).

As Jung realized, the proclamation of this dogma heralded the rise of the feminine in modern Western culture by emphasizing that it is a woman who is, par excellence, what each of the faithful is called to become. What's more, I've often wondered why women almost always outnumber men in church settings. Having pondered Jung's words, I think it's just because the feminine in each of us is more apt to receive the man Jesus Christ into our hearts. In a sense, we are all feminine to God's masculine.

Satan, leader of all who rebel against God, is both frightened and shamed by the Queen of Heaven. That's all the more reason to attach ourselves to her.

Sunday, August 14, 2005

The Real "Matrix"

Get this from The Washington Times: "An edgy poster showing a somber Catholic priest in full black cassock and sunglasses posed like "The Matrix" star Keanu Reeves is proving so popular that the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has snapped up 5,000 of them." Those copies are arriving in Cologne for World Youth Day, which starts tomorrow. I hear the scoffing, of course: another feeble marketing gimmick to arouse interest in a life with long hours, no sex, and commitment to preaching unfashionable doctrines. But something is stirring; incredibly enough, it's been gaining momentum since the clerical sex-abuse scandal exploded in 2002.

The article also notes what nobody denies: "The Rev. Edward Burns, executive director of the USCCB's secretariat for vocations and priestly formation, said 544 men were ordained by U.S. dioceses in 2004, compared with 449 men ordained in 2003. " Judging from the rate of seminary applications, the uptick is almost certain to continue. That doesn't just reflect the increase in what used to be called "late" vocations; it runs across all eligible age groups. Many of the younger men are motivated by the ideal of heroism imbibed from movie icons such as Neo of "The Matrix" and Gandalf, leader of the forces of good in The Lord of the Ring trilogy. (Those of us who were reading Tolkien decades ago apparently didn't get it well enough.) Think about it: these guys actually see the priesthood as a hero's life of fighting for good against evil. No stuffed shirts looking for sinecures, they. And they're right: if one loves Jesus Christ at all, then one takes his mission and his doctrine seriously enough to embrace heroism as what's required to dedicate one's life to him. In a world where the contrast between good and evil is ever starker, the seminary and ordination stats are starting to reflect such renewed motivation.

For Catholics of my generation, the baby boom, this is nothing short of amazing. Most of us were too caught up in the sexual revolution even to consider, much less handle, the idea of celibacy for the sake of the Kingdom. Our parents hardly discouraged us as they muttered bitterly about the bad old days of no birth control and no divorce. Well, a generation of birth control, divorce, materialism, and assorted other ills has produced a backlash among Gen-X and even younger men. They find nothing inspiring in the ethos of secular hedonism. The best of the recent epic and adventure movies are clearly speaking a different message to their hearts. Some actually want to give themselves as gifts to The Mighty and Eternal One. And the gifts are falling right into the laps of the often-hapless bishops.

"Where sin abounds, grace abounds still more."

Saturday, August 13, 2005

Newspeak is not fantasy

Such is one outcome of documented, across-the-board efforts at the Times to maintain fairness and objectivity in how it reports on controversial issues. On many issues such efforts bear fruit, but not on this one. Try as they might, they just can't bring themselves to make the slightest concession to ways of speaking about abortion that might humanize the conceived child in the womb. That is why, says Woodward, when legislation on abortion is the news, it is almost always depicted in the media as “restricting” abortion rights, when in fact such legislation could, with equal justice, be described as “protecting” unborn life. In the MSM generally, it apparently won't do to acknowledge that there could be a life objectively worth protecting whether or not the mother sees it that way. An unborn child is only a person if its mother, for reasons of her own, chooses so to regard it; if she doesn't, it isn't. (Gee, there's a whole bunch of things I wish I could make so just by wishin' and believin'. Anybody in favor of equal rights for men in that department?)

Coverage of partial-birth abortion has made such ideological use of language particularly clear. Proponents and opponents are speaking different languages. The language of the opponents is closer to the physical reality. All across the larger abortion debate, it is closer to the spiritual reality as well. Which is why the proponents of abortion won't use such langauge themselves.

Similar tactics by pro-life groups are considered evidence of "fundamentalism." Tu quoque?

Thursday, August 11, 2005

Blackmailed for existing

It would appear that the Chinese Government's one-child-per-family has had two major effects beyond population control. (See the Zenit story.) One has been fairly widely noted by sociologists: because of the traditional preference for boys, the number of men in the rising generation will be markedly greater than that of women, thus leaving many decent men all but unmarriageable. Large numbers of unattached and unattachable men is by itself a recipe for considerable social unrest. But another effect has gone virtually unnoticed: many children of both sexes who are not their parents' first are born but, given mandatory legal abortion for any conceived children beyond the first, are left entirely unregistered with the authorities. Their very existence is illegal. That has begun to create an underclass easily exploited through blackmail. Taken together, the two classes of rejects cannot but constitute a powderkeg.

That may well have far more lasting and far-reaching effects than the religious persecution and bureaucratic corruption that also characterize the current regime. I used to worry that China would establish itself as a superpower to rival or surpass the United States. I now worry that it may do so in terms of social disintegration.

A bright spot: At least the number of Christians now outstrips the number of Communists.

Wednesday, August 10, 2005

Irony-deficient editing

A 13-year-old giant panda gave birth to a cub at San Diego Zoo, but a second baby died in the womb, officials said Wednesday."--Associated Press, 3 August 2005

A cancer-ravaged woman robbed of consciousness by a stroke has given birth after being kept on life support for three months to give her fetus extra time to develop."--Associated Press, 3 August 2005

Sigh. Hat tip to Diogenes at Off the Record.

"The more things change..." department

Christianity taught that men ought to be as chaste as pagans thought honest women ought to be; the contraceptive morality teaches that women need to be as little chaste as pagans thought men need be.

—G.E.M. Anscombe, "Contraception and Chastity" (1972).

Tuesday, August 09, 2005

St. Edith Stein: the whole enchilada

Today is the feastday of a remarkable 20th-century saint whom the philosophical and literary cognoscenti savored for other reasons until she was canonized by John Paul the Great in 1998 under her professed religious name 'Teresa Benedicta of the Cross'. Since then, pretty much only conservative Catholic cognoscenti (and a few Jewish converts, which is what she was) talk about her. Yet canonized or not, Stein's life, work, and person repay pondering by women and men, by the uneducated as well as the educated, by non-Catholics and unbelievers as well as by Catholics.

Today is the feastday of a remarkable 20th-century saint whom the philosophical and literary cognoscenti savored for other reasons until she was canonized by John Paul the Great in 1998 under her professed religious name 'Teresa Benedicta of the Cross'. Since then, pretty much only conservative Catholic cognoscenti (and a few Jewish converts, which is what she was) talk about her. Yet canonized or not, Stein's life, work, and person repay pondering by women and men, by the uneducated as well as the educated, by non-Catholics and unbelievers as well as by Catholics.The exception to the newfound silence is the gleeful, occasional assertion by the Church's cultured despisers that the Nazis murdered her not for her intense Catholicity but for her ethnic Judaism. Of course it was probably both; which was the icing and which was the cake, we will probably never know in via. But I suppose the standard line makes a perverse sort of sense in a world where the formal recognition of one's sanctity by the Catholic Church is virtually a guarantee of social and intellectual irrelevance—unless the saint happens to have died a very long time ago, in which case they can be abstractly admired from a safe temporal distance. Yet even Stein's sisters in the older Catholic religious orders don't much care for her either. That's because she rejected women's ordination after having had the then-rare temerity to consider the idea in the first place. I've even heard one feminazi nun say (a) that's probably why JP2 canonized her and (b) that's exactly why he shouldn't have. All I can say is that my talents as a parodist can't quite match that.

The more I learn about this saint, the more stupefied with admiration I become. I first learned about her in college: I was reading her intellectual mentor, the German philosopher Edmund Husserl, for a course and was led by an editor's footnote to a long quotation from her book Finite and Infinite Being (now available only from the Carmelite publishing arm, information about which is included in the article I link to below.) I loved the chapters I read from that work because, unlike that of most European philosophers since the 17th century, her style is so pithy and her arguments so perspicuous. I didn't know then that she had become a nun and a martyr. A great mystic as well as a great intellect, she gave up an enormous amount personally to become Catholic and an equally enormous amount professionally to become a contemplative nun. And it is typical of the divine sense of humor that she got mostly grief for it all, right up to and including her death.

Philosopher, Jew, mystic, convert, consecrated religious, martyr: it's staggering how many gifts she rolled into one rich whole. I could go on and on, but it's absurdly late; so for now, I content myself with recommending Laura Garcia's 1997 article about her, which also contains a bibliography and other useful info.

Monday, August 08, 2005

Setting off the time-bomb

George Weigel, John Paul the Great’s official biographer and a prominent Catholic thinker on his own account, once remarked that the late pope’s theology of the body is a “theological time-bomb set to go off” in the Church. Yet so far I hear only muffled, intermittent ticking. If Catholics—and for that matter, Christians in general—are to start appreciating the true basis and beauty of the Church’s ancient teaching about human sexuality, the bomb must be set off. And such appreciation is long overdue in an era when Christians, by and large, are less disposed than ever to live by such teaching. In my opinion, that is one of the major obstacles to effective evangelization in the world today. We need to re-evangelize ourselves in this area at least as much as any other. As far as I’ve seen, the theology of the body is the only way on offer.

I started this blog a few months ago largely to provide a convenient medium for developing my thoughts and garnering feedback on this very topic. That I have received no feedback thereon is mostly my own fault; my largest entry, which consists of the first half of an article on the topic I was writing for publication, has long since got buried in archive and I haven’t even reached the punch line yet. But that little experience, I’m afraid, is all too typical of the larger Catholic experience over the generation since Karol Wojtyla first propounded TOB at length in his teaching capacity as pope. Throughout the Catholic world, only a minority seem even to be aware of said theology, and fewer still take the trouble to absorb it. I used to think that was due to poor publicity, which left unmarked its great depth, beauty, and creativity. But I now believe the relative silence is explained largely by those very qualities. Coming to terms with the theology of the body would take most Catholics too far from their comfort zone, in which adult religious education is considered a leisure activity for the few and the Church’s moral strictures about sex are often compromised when not ignored. That needs to change. What can be done to change it?

Part of it is simply the dog-work of getting the message out. The message is not hard to put succinctly and attractively. Thus:

The Pope’s thesis, if we let it sink in, is sure to revolutionize our understanding of the human body, sexuality and, in turn, marriage and family life. “The body, and it alone,” John Paul says, “is capable of making visible what is invisible, the spiritual and divine. It was created to transfer into the visible reality of the world, the invisible mystery hidden in God from time immemorial, and thus to be a sign of it” (February 20, 1980).That’s from America’s leading popularizer of the theology of the body, Christopher West. It just scratches the surface, but it presents a surface well worth getting beneath. The only people I’ve encountered who actively dislike the theology of the body are Catholic theologians who have long opposed the Magisterium for reasons of their own; almost everybody else to whom I’ve shown it approves it. Some are even excited by it.

A mouthful of scholarly verbiage, I know. What does it mean? As physical, bodily creatures we cannot see God. He’s pure Spirit. But God wanted to make His mystery visible to us, so He stamped it into our bodies by creating us as male and female in His own image (cf. Gen. 1:27).

The function of this image is to reflect the Trinity, “an inscrutable divine communion of [three] Persons” (November 14, 1979). John Paul thus concludes that “man became the ‘image and likeness’ of God not only through his own humanity, but also through the communion of persons which man and woman form right from the beginning.” And, the Pope adds, “on all of this, right from ‘the beginning,’ there descended the blessing of fertility linked with human procreation” (ibid.).

The body has a “nuptial meaning” because it reveals man and woman’s call to become a gift for one another, a gift fully realized in their “one flesh” union. The body also has a “generative meaning,” which (God willing) brings a “third” into the world through the couple’s communion. In this way, marriage constitutes a “primordial sacrament” understood as a sign that truly communicates the mystery of God’s Trinitarian life and love to husband and wife, and through them to their children, and through the family to the whole world.

This is what marital spirituality is all about: participating in God’s life and love and sharing it with the world. While this is certainly a sublime calling, it’s not ethereal. It’s tangible. God’s love is meant to be lived and felt in daily life as a married couple and as a family. How? By living according to the full truth of the body.

Many are not excited because they see little reason to immerse themselves in what strikes them as another lengthy, head-hurting theological case for avoiding what they like. But for people whose souls are larger than that, the theology of the body is peerless as a place to begin reinvigorating their understanding of what the gift of sexuality is really about. Healthy theologians can and do appreciate it as a way of incorporating the Catholic Church’s traditional natural-law approach to sexual questions into the overarching personalism of biblical revelation. I invite readers to study the theology of the body and register reactions once they have done so. Those already familiar with it, if any, would be of great help.

The above is a slightly edited version of a piece I posted at Pontifications.

Sunday, August 07, 2005

Could this be literally true?

Friday, August 05, 2005

It isn't about us

With his usual insouciant wit, John de Fiesole over at Disputations has reminded me of something that many never learn and that I often forget. Sometimes I even regret forgetting it.

Last year, as I was participating in a luncheon-seminar at a Franciscan ministry center, a dismaying thought occurred to me: we're all talking as though the Christian life is about us! Of course it isn't, in the end; it's about Christ, "through whom and for whom" all things were created and into whom the members of his Mystical Body, the Church, are incorporated. Indeed the only point of view that yields the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, thus revealing the full significance of things, is the God's-eye point of view. For that reason, we should learn as disciples to see with Christ: sub specie aeternitatis. Now since we're not quite God even as we share in the divine life, that vantage point will never be fully attainable; so after the occasion I chatted briefly with Fr. Louis Canino, the host, and opined only tentatively that we all need more of something I couldn't find a better word for than "objectivity." I assured him that I didn't mean a dry, academic objectivity, although some people could assuredly benefit from more exposure to that; I meant that our field of vision should be bigger than it usually is and should radiate outward not from us but from Christ. He agreed and suggested I write an article about it. But since I hadn't yet embraced what I was recommending, I replied by telling him that I was more likely to mollify Child Support Enforcement if I got a better-paying steady job.

Now that I'm duly chastened by learning how narrow my vision is, I think I'll write that article. Suggestions would be welcome.

Thursday, August 04, 2005

Creative theologizing on the single life

I've finally found an article that seems to be on the right track. Please click the link and check it out. I don't know whether it's creative in itself or more a popularization of some theological proposal. Perhaps somebody out there could enlighten me.

Roberts: unBorkable but unreliable?

For pro-lifers, especially us Catholic ones, the key question about President Bush's nomination of Judge Roberts to the Supreme Court is simply this: will we be fooled again? Is Roberts really one of us, who has merely been cagey enough to leave too limited a paper trail to get Borked by the Senate Democrats? If so, then Bush's choice is nothing short of brilliant. Or will Roberts turn out to be as disappointing on Roe v Wade, if confirmed, as his promise to "respect settled law" suggests? Is such a promise merely a clever, tactical way to maintain plausible deniability of any intent to overturn Roe, or does it indicate that he is really disinclined to overturn Roe? If the former, then he's being deceptive if not downright dishonest; if the latter, then he's part of the larger problem, not part of the solution.

I suppose politics inevitably generates such dilemmas, which is one reason I've never been inclined to make a career of it. But I pray that, once on the Court as now seems likely, Roberts is duly influenced on Roe by his fellow Catholic justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas. He has a very heavy responsibility that his knowledge and practice of Catholicism leave no room for evading. I hope the Pope privately reminds him of that. The only other ground for optimism I can find lies in the loophole that Roberts has left for himself.

His express concern with "maintaining the stability of the legal system" is logically compatible with, among other things, regarding Roe as a decision which upset said stability. That decision has been broadly criticized in the legal profession in the same way as Justice Byron White did in his 1973 dissent from Roe, where he excoriated the decision as "an exercise of raw judicial power" without any clear basis in the Constitution. It is plausible to me that Roberts would agree and vote accordingly while thus keeping his promise.

I keep my fingers crossed and my rosary in hand.

Monday, August 01, 2005

Scottish MP has vivid mystical vision

For years I've been fascinated with NDEs. Though I'm willing to entertain the idea that many are due to changes in brain chemistry in extremis, I find myself unable to explain away all similar experiences in that fashion. They occur under too many different conditions, are way too coherent, and are undergone by too many emotionally stable people, to be dismissed as endorphin-induced dreaming.

One example is what happened to Lord Rannoch, a prominent Euroskeptic and member of the British House of Lords. Read the account for yourself. I'm interested in two points: the message Lord Rannoch alleged he was given, and the conclusion he drew.

The message is, or was said to have been, that "God was sad because he was losing the fight of good against evil and sad because people have lost faith." With qualification, I believe that was the actual divine message. I qualify because I don't believe it possible that God will actually "lose" in the end; at most, his "losing" means that evil appears to be winning the day, just as it did at the crucifixion of Jesus. But it's certainly true in Europe and the English-speaking countries that people have lost faith—though even there one might argue that it's not true to the same extent in the U.S. I believe that Jesus Christ is sad, roughly for the reasons Lord Rannoch reports.

But what practical conclusion does the peer draw? "It has given me a greater awareness of issues of right and wrong and has also made me pretty fearless....I don't mind taking on the House of Lords on an issue about Europe even if it means I will be ridiculed and despised because it is part of the crusade of right against wrong..." Sheesh. I appreciate Euroskepticism but I hardly consider the battle over British integration with the EU to be one of eschatological significance. Even the moral contours are not altogether black and white.

Perhaps it is just such egoism that explains why politicians almost always make poor evangelists, even though some ministers, such as Martin Luther King, have made effective politicians.

The "theology" of gay marriage

Last week I came across yet another argument for gay marriage. It is noteworthy because it is not couched in the usual political language of equal rights and personal autonomy; the use of such language assumes that it is up to the state to define (as distinct from regulate) marriage, and is thus question-begging when not completely irrelevant. But the argument of note is, in effect, that on an orthodox understanding of the relationship between Christ and the Church, same-sex marriage is every bit as sacramental as marriage in the ordinary sense. That is quite relevant. It is also profoundly deceptive.

The author, Todd Bates, summarizes the argument as follows:

1. Christ was resurrected in the flesh, and will exist in the world to come.Now Bates takes some care to explain each step, and I shall not presume to gainsay the explanation. (It is, after all, his argument.) He seems to believe that one of the argument's key advantages is its sharing its premises with otherwise orthodox (what CS Lewis called "mere") Christian theology. That seems to put the burden on the mere Christian to show why the conclusion doesn't follow. And that burden is daunting, since Bates' argument appears to be formally valid. But the difficulty with the argument is not hard to specify; ironically, it is with the one premise that Bates seems to think requires no explanation.

2. In the world to come, members of the Church will be resurrected, male and female, in the flesh.

3. In the world to come, the members of the Church will bear a new real, reciprocal relation to Christ; call it R.

4. Here below, marriage should be modeled on R.

5. R obtains between males: for instance, Christ and each blessed male.

6. As R obtains between males, and marriage is to be modeled on R, marriage may obtain between males.

The difficulty is with (5): specifically, (5) is ambiguous. It does not distinguish between Christ's relation to members of the Church taken collectively and taken severally. It assumes that relevant relation holding between Christ and the Church qua whole is exactly the same as that holding between Christ and each member of the Church qua individual. In context that assumption is easy to make, inasmuch as the union-in-love that will obtain in the Eschaton between Christ and the Church qua whole will certainly be manifest in how it obtains between Christ and each saved human. But from the fact that marriage is a sacramental sign and foreshadowing of R, and that R will obtain between Christ and the Church qua whole, it does not follow that precisely R will obtain between Christ and each member of the Church individually. Indeed one cannot assert, as a general proposition, that any relation holding between a given x and some whole W is exactly the same as that holding between x and each part of W. Such identities can and do sometimes obtain, but not always by any means. And so (5) is far from trivial: Bates needs an argument to show that the relevant relation between Christ and each individual member who is saved will be exactly the same as that which will hold between Christ and the Church qua whole.

The first thing such an argument would have to show is that same-sex marriage, contra the tradition and teaching authority of the Church as well as Scripture's condemnation of sodomy, is in fact possible. In the context of mere Christianity, that is no small task. In fact there are good grounds for holding that same-sex marriage is impossible; see William May's On the Impossibility of Same-Sex Marriage.

Bates needs a dose of John Paul II's "theology of the body"—as do Christians in general today. It is so much more profound and healthy a vision of human sexuality than most of what we get these days.