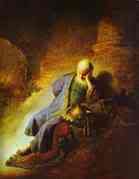

So reads Jeremiah 20:7, from the readings at Mass celebrated in the normative rite of the Latin Church today. Indeed the entire reading from Jeremiah today is one of my favorites from the Bible; I like to meditate on it in conjunction with Isaiah 55: 6-11, which is my absolute favorite reading from the Bible. But today I want to focus on a central theme of the Mass readings.

So reads Jeremiah 20:7, from the readings at Mass celebrated in the normative rite of the Latin Church today. Indeed the entire reading from Jeremiah today is one of my favorites from the Bible; I like to meditate on it in conjunction with Isaiah 55: 6-11, which is my absolute favorite reading from the Bible. But today I want to focus on a central theme of the Mass readings.Jeremiah and the Apostle Peter (see today's Gospel reading, linked above) had in common an initial, and of course quite natural, inability to understand or appreciate the importance of suffering in the spiritual life. In that respect, they represent all of us. We abhor suffering and thus tend to flee it; if we didn't, it wouldn't be suffering. Jeremiah's prophetic words, which he knew were from God and felt compelled to proclaim, earned him fierce opposition and derision; according to rabbinical tradition, he was eventually murdered by his countrymen in Egypt, where he had taken refuge from the conquest and razing of Jerusalem by King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. But well before that he had to struggle not to become bitterly cynical about the God he obeyed. He didn't quite get the point of being rewarded for his fidelity with as much misery as he predicted, correctly, his fellow Jews would get for their infidelity. But he apparently never lost the conviction that there was a point.

Peter didn't get it either in the case of his beloved friend and master, Jesus of Nazareth. Naturally, Peter want Jesus to triumph as the king he was by right rather than be killed as a public nuisance. Peter didn't understand until after the Ascension what is now a flip truism: "No cross, no crown"—or, to put it in debased secular form: "No pain, no gain." No more than Jeremiah did he appreciate the ironic sense of humor shown by a God who saved his people, indeed the whole world, by getting himself tortured and executed by them and thus taking the punishment that was theirs.

But of course the logic of the thing is unassailable once the premises come from God not man. As Jesus said: For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it,but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. Why? Our life in this vale of tears is fatally flawed by original and actual sin; clinging to it—i.e., living "in the flesh" rather than "in the spirit"—implicates us hopelessly in the spiritual death that caused physical death to enter the world. To enjoy the life God has planned for us from all eternity, we must accept suffering as the negation of what is fatally flawed about ourselves. That is what teaches us the detachment necessary for dying to self in order to live for God. The seed must "fall to the ground and die" before it can bear lasting fruit.

Such, in effect, is St. Paul's advice in today's second reading:

I urge you, brothers and sisters, by the mercies of God, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God, your spiritual worship. Do not conform yourselves to this age but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and pleasing and perfect.

The "renewal" of our minds Paul urges is a radical re-orientation, entailed by repentance and conversion, about suffering. Our supreme rule of living is no longer to be the pleasure principle but rather the high priesthood of Christ, who is as much victim as priest and is priest precisely because he has been victim. That is the pattern to be emulated by all the baptized, who form the Mystical Body of Christ. That is what the "priesthood of believers" consists in. It is not an opportunity to wield authority in the Church, though a few are granted that privilege and should accordingly tremble. It is an opportunity to become like Christ in the large and small matters of everyday life.

An attitude like that doesn't come naturally; it is a supernatural gift that must be gratefully accepted and earnesty cultivated. Most of us fail often to do so; I know I do. But I pray for the help to get up and resume the renewal of my mind; the more God grants that prayer, the more abject my failures seem, both large and small; yet the more glorious the real potential for growth also seems. Each of us knows how to enter into that pattern if we're willing to listen to the Holy Spirit. Like many men in this world, I find that my job helps.

The work is the pain; the paycheck is the gain; and even a substantial portion of the latter goes, directly or indirectly, not for my own gratification but for the needs of others to whom it is due as simple justice. All that is normal and apparently unremarkable. But I wouldn't be able to get through a day without remembering that it is a very important way in which I exercise my priesthood. Each in their own fashion, everybody has the opportunity to die and thus live. Suffering is unavoidable; we can either use it well or bring more of it on ourselves by our refusal to use it well.

For the sake of finding our true lives and homes, we must take the opportunity early and often.