Sunday, February 22, 2009

What Do the Readings Really Say?

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Dr Witt on material & formal sufficiency

It goes without saying that WW's position and mine are mutually incompatible. I am a Roman Catholic; he is a conservative Protestant of the sort who, in my previous post, I identified as an adherent of the Protestant "hermeneutical circle." And yet, for reasons I have yet to fathom, he tries to enlist St. Thomas Aquinas in his cause. Thus WW:

I think the real issue of disagreement has to do with the question of the inherent intelligibility of Scripture. Followers of Newman often speak of the sufficiency of Scripture in terms of a “material” sufficiency. On the page on my blog titled “Who Are Those Guys?” I speak of how, as I read Aquinas, Arminius and Barth, they do theology as a penetration into the mystery of the inherent intelligibility of revelation as witnessed to in Scripture. I see the same kind of approach in Eastern theologians like Athanasius or Cyril of Alexandria.

Such an understanding of Scripture’s inherent intelligibility presupposes that the sufficiency of Scripture is not material, but formal. The difference here is between a blueprint to make a building, and the bricks of which the building is made. A merely materially sufficient Scripture is like a pile of bricks that can build anything from a cathedral to a tool shed, but the bricks themselves possess no inherent intelligibility (formal sufficiency) in one direction for another. The intelligibility derives from outside the bricks. Conversely, a blueprint is inherently intelligible, and thus has not material but formal sufficiency to create a specific building, whether cathedral or tool shed.

In terms of development, the claim that Scripture is materially sufficient presumes that the intelligibility of revelation derives from elsewhere than Scripture itself. A definitive magisterium (or external tradition) is necessary to decide what to do with the bricks. Without the magisterium it is impossible to know whether the bricks were intended to be a cathedral or a tool shed.

I cannot comment on Arminius and Barth, Protestant theologians whom WW knows far better than I. But for starters, I can and will say and unequivocally that Aquinas, while indeed affirming the "material sufficiency" of Scripture in the sense explained by WW, in no sense affirmed the formal sufficiency of Scripture. That is partly why Aquinas, like Newman and even Vatican II after him, most certainly did see a magisterium as necessary for interpreting Scripture reliably.

Consider this from ST IIaIIae Q5 A3 resp (emphasis added):

Now the formal object of faith is the First Truth, as manifested in Holy Writ and the teaching of the Church, which proceeds from the First Truth. Consequently whoever does not adhere, as to an infallible and Divine rule, to the teaching of the Church, which proceeds from the First Truth manifested in Holy Writ, has not the habit of faith, but holds that which is of faith otherwise than by faith.

The context of the questio from which the above quotation is taken suggests that we may put Aquinas' point as follows: Although it is quite possible to discern "the First Truth" in Scripture without adhering "to the teaching of the Church as to an infallible and divine rule," one can only do so as a matter of opinion rather than by the virtue of faith. Hence, even if Scripture is somehow "inherently intelligible," one who affirms the truth that is intelligible in Scripture while rejecting the Magisterium has only a set of opinions about the content of the deposit of faith, rather than the kind of certainty entailed by true faith. I agree with that view. As far as I can tell, it was the view of John Henry Newman too. As for Vatican II, see Dei Verbum §7-§10.

The distinction between apprehending the "First Truth" by opinion and doing so by faith may seem irrelevant to some, but it is actually of the utmost importance. Opinion is fallible and provisional, whereas the content of the deposit of faith, as the proximate object of the theological virtue of faith, is not and cannot be a matter of opinion. Many people imagine that one can get around this by saying that Scripture is "formally sufficient" for expressing the DF and making assent to its content a matter of faith. This would mean that, for purposes of apprehending the DF by faith, nothing need be added to what Scripture explicitly says; all one has to do is "get" the blueprint, perhaps as a kind of gestalt perception, and the rest follows. But that, in my view, just isn't credible.

Protestant scholars of WW's bent are forever frustrated and disappointed by the fact that even those Protestants who would, in general, agree that Scripture is "inherently intelligible" at some architectonic level—and might even find the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed helpful—often hold or reach doctrinal conclusions so different as to be, or become, church-dividing. Thus even when they do agree, the agreement doesn't last long enough to prevent others from eventually dissenting, hiving off to form their own church, and leaving a rump behind to rest on the old, unrevised "confession." Given the denominational proliferation occasioned by such differences, it would seem that Scripture, though inherently intelligible, is actually intelligible only to—well, to whom? That's my point. WW and some others seem to believe that if only Protestant church authorities would recognize and accept the best scholarship—as understood and expounded by men such as himself—and were willing to inculcate its results firmly enough to keep the pastors convinced enough to teach faithfully enough to keep the faithful convinced enough, then the inherent intelligibility of Scripture would shine forth globally enough to constitute actual intelligibility. In fact, WW seems to believe that something very much like that happened during and after the roaring, sometimes violent theological controversies of the fourth and fifth centuries. Thanks to men such as Athanasius, the Cappadocians, and St. Cyril, the Trinitarian and Christological orthodoxy that was painfully hammered out during that time demonstrated the inherent intelligibility, and therefore the formal sufficiency, of Scripture as a proximate object of faith!

Right?

I apologize to some if I've already overstated the irony, but others might need to have it pointed out. Almost a century-and-a-half of intellectual effort was needed to overcome the pre-Nicene theological vagueness, itself almost three centuries old, that occasioned Arianism and other forms of subordinationism. Was the resulting clarity and cogency really so great that Christians no longer needed to defer to the authority of general councils in order to identify the "orthodox" faith? Was it just obvious, by the latter part of the fifth century, that the credibility of orthodoxy consisted so much in its hermeneutical superiority to the alternatives that simple obedience to ecclesial teaching authority was unneeded? To anybody who knows church history, such questions virtually answer themselves. There were "heresies" not only before and during but also well after Nicaea and Chalcedon—and there still are. Indeed, as Dorothy Sayers so wittily showed, many people today (Catholics as well as Protestants) who accept and read the Bible as the Word of God also adhere to one of the ancient heresies without realizing it. But if Scripture were intelligible in the way and to the degree that WW says, then the cure for heresy would simply be a more thorough, more prayerful reading of the Bible. The failure of such a cure could only be explained by lack of "education" or, perhaps, sheer cussedness—i.e., by the kinds of factors which Protestants in the mid 1500s were already citing to explain their own divisions, even leaving aside their issues with the Whore of Babylon, aka the Church of Rome.

Well, it's not always or even usually like that. Even when people read the Bible correctly, and thus hold what is "of faith," they do not do so "by faith" unless they let themselves be guided, implicitly or explicitly, by the living, authoritative voice of the Church. Otherwise, even God's own truth can only be held as one opinion among others, and is thus legitimately susceptible to reversal (where have we heard things like: "The Holy Spirit is doing a new thing"?). At least that's what Aquinas thought, and I believe it.

Even so, I think even Aquinas went too far in affirming the "material sufficiency" of Scripture. For Scripture can be seen as the inspired word of God only because the same Holy Spirit who inspired it had the Church certify the writings it comprises as the pre-eminent written record of "Tradition" (i.e. of all that was handed down from the Apostles under his guidance) that could be read aloud in church. Scripture is therefore not, as the cessationists would have us believe, substitutable salva veritate for Tradition; it only constitutes the Word of God for us together with Tradition. I can therefore accept the joint material sufficiency of Scripture and Tradition, but not their separate material sufficiency. And to get formal sufficiency?

You need what Aquinas says: adherence to the teaching of the Church as to "a divine and infallible rule." I said that's what you need; I didn't say that's all you need. I like my CCC for that. But even the CCC...

Sunday, August 24, 2008

The paradox of Peter

The Gospel reading for today in the ordinary form of the Roman Rite is Matthew 16:13-20. It contains one of the most famous passages from the New Testament: "You are Peter (Kepha), and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it." I am not concerned here to explicate the sense in which that verse supports the Catholic doctrine of the papacy. That would only invite a debate that has and will continue to take place in countless forums, including this one. I am much more interested in the attitude the verse ought to encourage in every Christian.

Jesus' commissioning of Peter as the Church's "rock," as "Rocky," in response to Peter's inspired confession of faith, was deeply ironic. Peter was impulsive and inconsistent. At one point, Jesus addressed him as "Satan" for rejecting the idea of the Passion; as the Passion got underway, Peter thrice denied knowing Jesus. But all this is exactly what one should expect of a God who saved us by letting us put him to death in the most shameful way imaginable at the time. God meets us in our worst depths to elevate and transform us; in his humanity, he was raised up on the third day from the status of dead criminal to that of immortal King of the Universe. In his own small but indispensable way, Peter recapitulated that in his transformation, after Easter and Pentecost, from coward to rock of the Church.

The same should go for each of us in our individual journeys of conversion. I know what it is like, in my own little way, to be cast out, criminalized, and shamed to the depths; I know what it is like to be loved, elevated, and transformed by Our Lord precisely in and out of such circumstances. It is all part of the process of theosis, of being made into a god by participating in the eternal kenosis of God. The mold of the old self is broken and remade into something new and incomparably better, just as Peter was.

The Church herself is like that. She is a "perfect society" not because her members are perfect; far from it. She is the perfect society because, as the Mystical Body of Christ, she is the medium in which her members are taken in their brokenness and made whole on the model of the Passion and Resurrection. If people would come to see "church" in that way, rather than as just an institution whereby a bunch of people with similar religious opinions worship and do other things together, there would be a lot less disputing about the full meaning of Matthew 16:18.

Sunday, June 22, 2008

The right kind of consumption

The "responsorial psalm" at today's Mass got me thinking and praying. This part in particular, from Psalm 68:

The "responsorial psalm" at today's Mass got me thinking and praying. This part in particular, from Psalm 68:For your sake I bear insult,

and shame covers my face.

I have become an outcast to my brothers,

a stranger to my children,

Because zeal for your house consumes me,

and the insults of those who blaspheme you fall upon me.

I was given to realize two things: that the above has, in due time, applied to me, and that I had nothing to do with the "zeal" in question. Indeed, not only can I take no credit for having been ostracized; what contributed most to my greatest ostracization was my own, earlier resistance to the zeal that was consuming me. So, I don't merit victim credentials on anything like the order of the psalmist's, or the prophet Jeremiah's.

Even so, I suspect that if the above psalm verses don't apply, in some measure and fashion, to each confirmed Christian, they're not doing their job.

Sunday, June 15, 2008

Why we need to be more Jewish

Here's the first Scripture reading at today's Mass (Exodus 19: 2-6):

With all their suffering, sinning, and exile since then, it is faith in that divine promise which has kept the Jewish people alive. A similar faith is needed to keep the Church, the New Israel, relevant in today's world.

On the whole, the ancient Israelites did not much like their vocation. Many fell away; even in the Sinai desert, those who didn't fall away had to endure "forty years" of wandering there—i.e., a heckuva long time—as the price of their grumbling half-faith. The Church as a whole, as People of God, resembles them; each of us sinners, as individuals, resembles them. God has called us out of slavery to a sinful world into a desert of dispossession where we can be free to hear his will for us and act accordingly as his priests for the world. He knows we cannot do that ourselves; so, by a continuous miracle of grace, Christ the One High Priest makes it possible for us. But on the whole, we aren't grateful. We think it's too hard, and unfair, and we didn't ask for this anyway. When the day's manna is gone, we're not sure the next day's will come. After all, you can't get something for nothing; at least the Egyptians (the world) kept us alive for doing their work for them. And though we may have left our former taskmasters behind, there's always those nasty Amalekites waiting near the next wadi. Anything good is taken by sweat and blood. Not even God's going to let us out of that. This business about faith and the law that Moses and Aaron (the saints and the hierarchy) keep selling us only makes everything harder. Let's just be realistic and get back to ordinary life like other, saner, happier people. No more Catholic hangups for us.

I'm keeping things general because the ways in which we do that, as both church and as individuals, are myriad. The Church's most visible temptation to be like the faithless Israelites is the temptation of the hierarchy to preserve the Church's institutional apparatus, and therefore their perks, at the expense of true witness—and therefore at the expense of those in and out of the Church who most need that witness. That's happened time and again in Church history, the most recent example being the systemic coverup of the sexual abuse of minors. We always see that, in the end, it doesn't work. But there are other sins; and our sins precisely as ordinary lay people all add up to a refusal to belong to a nation of priests. Priesthood is the business of the pros, it is thought; I'm just an ordinary person who wants what's rightfully mine and, having got it, to be left alone by the religious fanatics. They need to stay out of the bedroom and the boardroom.

The Jews have always had a "faithful remnant"—sometimes smaller, sometimes larger—to carry on in spite of everything. Sometimes they had to carry on in spite of persecution from members of the New Israel. We Catholics need to adopt a similar mentality. There needs to be a faithful remnant—which can sometimes embrace those outside the Church's visible boundaries—to preserve the fullness of the faith and the determination to live lives that don't water it down. In our day and age, there is no longer a Catholic culture to ensure that we can do that if we want. Our lives of faith, hope, and love must be intentional and countercultural. If we stop whining long enough to trust, the One High Priest will make up for our inability to do it ourselves.

Friday, March 21, 2008

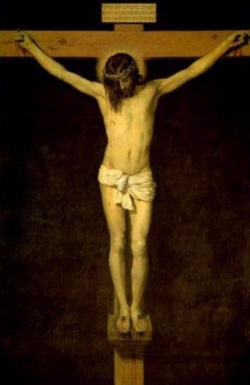

The key to the riddles

It is certainly not surprising that the disciples were able to understand the meaning of the Cross only slowly, even after the Resurrection. The Lord himself gives a first catechetical instruction to the disciples at Emmaus by showing that this incomprehensible event is the fulfillment of what had been foretold and that the open question marks of the Old Testament find their solution only here (Lk 24:27).

It is certainly not surprising that the disciples were able to understand the meaning of the Cross only slowly, even after the Resurrection. The Lord himself gives a first catechetical instruction to the disciples at Emmaus by showing that this incomprehensible event is the fulfillment of what had been foretold and that the open question marks of the Old Testament find their solution only here (Lk 24:27).Which riddles? Those of the Covenant between God and men in which the latter must necessarily fail again and again: who can be a match for God as a partner? Those of the many cultic sacrifices that in the end are still external to man while he himself cannot offer himself as a sacrifice. Those of the inscrutable meaning of suffering which can fall even, and especially, on the innocent, so that every proof that God rewards the good becomes void. Only at the outer periphery, as something that so far is completely sealed, appear the outlines of a figure in which the riddles might be solved.

This figure would be at once the completely kept and fulfilled Covenant, even far beyond Israel (Is 49:5-6), and the personified sacrifice in which at the same time the riddle of suffering, of being despised and rejected, becomes a light; for it happens as the vicarious suffering of the just for "the many" (Is 52:13-53:12). Nobody had understood the prophecy then, but in the light of the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus it became the most important key to the meaning of the apparently meaningless.

—from Hans urs von Balthasar, A Short Primer for Unsettled Laymen

Sunday, March 16, 2008

The fans and the mob

For reasons I won't waste your time speculating about, my mind returns every Palm Sunday to the contrast between the crowd's adulation of Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey with the venom of the mob calling for his crucifixion before Pilate a few days later. One thing I'm sure of is that both crowds are figurae, types, of own souls as they oscillate between grace and sin, between living, joyful faith and preference for the world's way of doing things. We welcome Jesus as our savior, yes; we also shout "Crucify him!" whenever we sin seriously, as most of us have done. I'd love to help do a movie in which a couple who had greeted Jesus with hosannas went on to join the crowd yelling for Barabbas' release instead of Jesus'. A plot premise would have them desperately poor, ripe to take a few shekels from the high priest's henchman for joining the mob. I have an old friend who could write a good script for such a movie. Of course there's always the matter of raising the money...

For reasons I won't waste your time speculating about, my mind returns every Palm Sunday to the contrast between the crowd's adulation of Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey with the venom of the mob calling for his crucifixion before Pilate a few days later. One thing I'm sure of is that both crowds are figurae, types, of own souls as they oscillate between grace and sin, between living, joyful faith and preference for the world's way of doing things. We welcome Jesus as our savior, yes; we also shout "Crucify him!" whenever we sin seriously, as most of us have done. I'd love to help do a movie in which a couple who had greeted Jesus with hosannas went on to join the crowd yelling for Barabbas' release instead of Jesus'. A plot premise would have them desperately poor, ripe to take a few shekels from the high priest's henchman for joining the mob. I have an old friend who could write a good script for such a movie. Of course there's always the matter of raising the money...Which brings me to my main point. The Jews weren't ready to accept the idea that God could come to them in person as a man who, sans army, formal education, or even money, would challenge their religious leadership rather than the occupying power. You can hardly blame them; they thought as people normally would. The Anointed One they expected would be a political savior. He would eject the Romans by force and turn Israel into a glorious earthly kingdom where other nations would worship God just as they did. That's what the Apostles hoped for too, which is probably why Judas was disappointed enough to betray Jesus when it had become clear that wasn't going to be the script. They didn't start to get it until Jesus appeared to them after the Resurrection; they didn't even understand, until well after the fact, that he had actually prophesied the whole thing. My friends, the Apostles are us.

We instinctively assume that good fortune consists in our obtaining the blessings the rest of the world considers blessings too. That's the movie we want to see, or better, to make. When we don't see it or have the wherewithal to make it, then God's script for us can be a bitter disappointment indeed. In response, some of us betray him and are lost, temporarily or permanently; many abandon him when the path of fidelity seems likely to yield, at best, a cruel joke. We return only when some grace, foreseeable yet unforeseen, brings us back round. Rare are the Marys and Johns who stand steadfast by him at the foot of the Cross. And even they often don't get to see, until their own passing, much of the Great Light to follow.

This Palm Sunday, I pray for the wisdom and courage to follow the script God is writing for me. I don't want to be tempted, any more than I already am, to leave the fans for the mob.

Sunday, March 02, 2008

When the blind need to lead the blind

Kirk to McCoy: "Well Bones, once again we've saved civilization as we know it."

McCoy to Kirk: "Yeah, and the best thing is they're not gonna prosecute."

If there's any justice, the man Jesus healed of congenital blindness wasn't prosecuted again for all the good he went on to do as a disciple.

Of course the Gospel passage itself drips with an irony long recognized. The man blind from birth does not at first know who "the Son of Man," the Messiah, is; in that sense, he is spiritually as well as physically blind. Yet he comes to "see" spiritually, by a faith elicited in turn by his being made able to see physically by Jesus; while the Pharisees, the educated and observant, don't see at all and in fact are made blinder still by their hardness of heart. Even as Jesus came to "open the eyes of the blind," he was to do so in such a way that those who "have eyes," and thus see, see not. All that is well understood; yet there are deeper lessons. I shall offer one I have been given to learn. But it will take a bit to work up to it.

It was assumed not only by the Pharisees but by Jesus' own disciples that the man's physical blindness was due to somebody's sin: his own or, perhaps, his parents'. The well-nigh universal assumption among the Jews at the time was that misfortunes such as birth defects, leprosy, even poverty had to be somebody's fault, so that the malady was just divine punishment. That's the flip side of the belief that caused the disciples to be astonished when Jesus told them how hard it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of heaven. Just as misfortune is a punishment for sin, good fortune is a reward for virtue. That was a very Old Testament view despite the alternative literature, such as Job and Ecclesiastes, that came to be canonized. Today we supposedly know better, at least if we are Christians. But do we?

How many of us ask ourselves "What have I done to deserve this?" when some major misfortune, or a steady series of misfortunes, strikes us! How many of us think well of ourselves when we have the things the world values! In this country especially, poverty is still thought of quite often as the due penalty for fecklessness, or some sort of spiritual weakness; those who become successful in the world's terms are assumed to have earned such good things by their merits. What makes such an attitude so seductive is that there is often an element of truth in it. When people are having a hard time, it is sometimes their own fault, at least in part; when people are enjoying the good things of life, it is sometimes because they have earned them, at least in part. That is a major reason why the prosperity gospel remains strong even among those who call themselves Christians; and in some of the more out-there New Age circles, there seems to be this idea that we somehow control whatever happens to us. But when being objective and honest, we recognize that much remains beyond our control. And many people are in lousy situations for which nobody in particular, beyond the effects of original sin, is to blame.

As Jesus' explanation of the man's blindness suggests, God's purpose in permitting such things is not to punish, but rather that his "mercy be shown forth." Ordinarily, that does not happen by miracles of healing. Padre Pio did once give sight to a blind girl born without pupils in her eyes, and there are other examples of things equally extraordinary in the history of the Church. But almost by definition, such events are extraordinary and thus rare. Ordinarily, God's mercy is supposed to be manifest by how we treat the unfortunate. That is how we are all called to bear Christ into the world. The mercy of God is shown by how we show his love to people regardless of how little they deserve it or how little we can get out of it. That is why those who find themselves summoned, by love or by work, to care for people who cannot care for themselves have such a great vocation. That is how people ordinarily "see" what God is. But even people with that vocation often overlook something that I too long overlooked: our first mercy must be to ourselves, by receiving God's mercy to ourselves.

Regardless of their formal religious belief or lack thereof, that is very difficult for a lot of people. As I get older, I become more and more convinced that "blame and shame" is the name of the game that most people are playing and/or defending themselves against. A lot of what's attended to in the workplace, for example, is sheer butt-covering: procedures whose purpose is not to produce anything but to ensure that the blame, if something goes wrong, falls—well, somewhere else. Since most of you have jobs, you needn't think long to see what I'm talking about. The same goes for domestic life. We all know families as well as workplaces where the first question asked when something goes wrong is not "What do we do about this?" but "Who did it?" But even if you are fortunate enough to have a job or family that isn't like that, it is often more difficult to forgive ourselves for wrongs we have done than to forgive others for how they have wronged us. I have heard more than one priest say that 90% of the problems that persist between people are due to unforgiveness. I think that's right—if one includes unforgiveness of oneself. So many people walk around burdened by guilt and self-condemnation, even those who profess belief in divine mercy. Sometimes the conscious reasons are quite specific; sometimes it's just a deep-rooted feeling of unworthiness, often caused by buried wounds from childhood or even infancy. But whatever the cause, a lot of people really do believe subconsciously something like: "There's no excuse for being who I am. I'm not worth much and probably deserve less." I speak what I know firsthand as well as what therapists and spiritual guides say about people.

The so-called "self-esteem" movement in education and parenting was meant to address that kind of problem. When it has any measurable effect at all, of course, such an approach tends to produce pampered narcissists ill-equipped to address real problems with courage and perseverance. What we need to do instead is recognize that our value comes from being conceived by the mind of God in boundless love. But that is not something humanity could have figured out for itself given enough time and research. Because of original sin, we start out blind to it and can only be assured of it by divine revelation. But many who have heard the Gospel are still blind to it. To be able to receive it, and the mercy on offer with it, we must admit our blindness to who we really are and humbly beg to be granted a personal encounter with Love Himself. Only those who admit they do not see Reality themselves can have that encounter. If they have it and respond accordingly, then those who think they see will be convicted of their own blindness. The blind who are brought to see must lead the blind who think they see. That is true evangelization.

Sunday, February 24, 2008

How many husbands have we had?

To the Jewish members of John's audience for his Gospel, his ascription of five husbands to the Samaritan woman at the well would have been well understood as an historical allusion to the five pagan gods, baals (lords), that the Samaritans had worshiped. As the late Raymond Brown pointed out in his commentary on this gospel, and as the Ignatius Bible also recognizes, the Samaritans were a mixed breed both ethnically and religiously. After the northern kingdom—"Israel" as distinct from the southern, "Judah"—had been vanquished and exiled by the Assyrians in the late 8th century BC, foreigners from five different districts were forcibly resettled among the Hebrew remnant. Intermarriage and religious syncretism produced what came to be known as the Samaritans, from the district in Palestine where they eventually concentrated. Relations between Jews and Samaritans had been execrable ever since Nehemiah expelled them from common worship when the returned Jewish exiles began reconstituting Israel. But common elements remained, especially the expectation of an anointed prophet, what the Jews called the Messiah. Jesus' conversation with the woman at the well, the same well where Jacob had met one of his wives, indicated not only that he was claiming to be the Messiah but was also the true Bridegroom of unfaithful humanity. Yet few of us love him as such, at least most of the time.

Most of the time, we trust more in other things: money, power, prestige, sex, science and technology, institutions—or, most seductively of all, people who actually do love us, such as parents or spouses. People who lack all such things are deemed pitiable; the prospect of having none of the above terrifies most of us; that's why trusting false gods comes more easily to us than faith in the true God. But when we trust more in what is not God than in God, we worship another god and are thus married adulterously. Spiritually speaking, we are bound to end up like the Samaritan woman—not even married to the latest "man," returning to the well over and over for the water of life. Temporal goods fail to satisfy our deepest longings. None of us will take them to the grave, even those fortunate enough to take some of them to the threshold thereof. Only Jesus satisfies our thirst; only Jesus is our true husband.

Yet his first words to the woman were: "Give me a drink." The difference between the Son of God and the false gods is that he thirsts for us, who can find him in those who thirst and meet him in slaking that thirst. We must see others like that. To do so, we must start with seeing ourselves like that. Only then can we get our marital status straightened out.

Sunday, February 17, 2008

Being God's works of art

Among the many works written by my first philosophy professor, Arthur C. Danto, is one called The Transfiguration of the Commonplace. It's an instance of the philosophy of art, one of his specialties. Such interest as I developed in that branch of philosophy, as distinct from the arts themselves, was aroused by that book. That was mainly because, in one of God's many little ironies, the title could just well apply to the spiritual life itself—even though art was about the closest thing to a religion that Danto had. Since today's Gospel was about the Transfiguration, I thought I'd say a bit more about how the title applies.

Among the many works written by my first philosophy professor, Arthur C. Danto, is one called The Transfiguration of the Commonplace. It's an instance of the philosophy of art, one of his specialties. Such interest as I developed in that branch of philosophy, as distinct from the arts themselves, was aroused by that book. That was mainly because, in one of God's many little ironies, the title could just well apply to the spiritual life itself—even though art was about the closest thing to a religion that Danto had. Since today's Gospel was about the Transfiguration, I thought I'd say a bit more about how the title applies.Unlike what is implied by many priests and theologians, I do not believe that every good thing is also holy or sacred. "The sacred" is a realm of being distinct from "the profane." From the standpoint of man's search for God, the sacred is that which man "sets apart" from the profane for representation of and/or service to the divine. Thus, people and things become sacred in virtue of being lifted out of the profane. The rituals in which such people and things serve a sacred function are themselves sacred because they are not ordinary, profane activities but rather ones in which some form of contact with the divine is sought. In natural religion, all the "profane" activities of life are valorized by being somehow related and oriented to the sacred activities. Now in the true, "supernatural" religion, revealed by God and thus signifying God's search for man, we also have sacred people, things, and activities. Human culture and convention play a part in all that. But they are ultimately established and given their meaning by God, and thus valorized, through Christ in the Holy Spirit. Our purpose in participating in them is to extend the Incarnation through the profane world by making Christ "be all in all," starting of course with ourselves. We are to become sacred ourselves so as to "transfigure the commonplace." If you like, we are to turn the world into God's work of art by first being his works of art.

Most lay people seem to have a very hard time grasping that. The most important human relationships, which occur in the "commonplace" spheres of family and work, are not often seen as that which we are destined to transfigure and thus make sacred. They seem to take their primary meaning from our secular and thus profane reality, and the best we can do with them spiritually is to try to follow "the rules" of Christian morality as we navigate through them, so that we aren't derailed by them. They remain profane in our consciousness and in reality; the "sacred" is reserved for liturgy, prayer, and maybe some volunteer activities. Among the truly "devout," this is rationalized by assuming that all the world is God's and everybody is a child of God, so that everything good is taken in theory to be sacred even if we don't often feel that in the realm of the commonplace. Such an attitude of course ignores the very real need for transformation: first, that of metanoia or conversion, a turning of the mind and heart to God; then, that of transfiguring the commomplace to serve the same purpose. If everybody and everything good is somehow sacred to begin with, then creation needs no transfiguring. God has done it already, to the extent it needs to be done at all; all we need to do is be nice and prosper.

That is illusion. To transfigure the profane as we are called, we must each undertake the journey of faith as Abraham did. We much each persevere, despite the deserts, the setbacks, and the unfairness of life, in the belief that God will make of us and our world something incomparably greater than we can see if we but conform ourselves to Christ. It's not easy to be God's work of art, or even to see how one is such a work in progress. Yet such is the meaning of the sacred, as opposed to the profane. We are set apart and thus sacred by baptism; but that is only the start of transfiguring the commonplace.

Sunday, February 10, 2008

There's temptation, and then there's temptation

The penance given me at my most recent confession was to pray the Lord's Prayer "slowly and meditatively." Of course, when I pray any traditional prayer in that way, it usually doesn't take me long to start mulling over its theological interpretation. In the present case, the issue was the closing two phrases. In the original Greek, that's καὶ μὴ εἰσενέγκῃς ἡμᾶς εἰς πειρασμόν, ἀλλὰ ῥῦσαι ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ τοῦ πονηροῦ; in Latin, ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo; in the King-James translation that English-speaking Catholics still insist on using, it's "lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil." Given that today's Gospel was Jesus' temptation by Satan in the desert, I thought I'd bring my internal discussion out into the open.

The penance given me at my most recent confession was to pray the Lord's Prayer "slowly and meditatively." Of course, when I pray any traditional prayer in that way, it usually doesn't take me long to start mulling over its theological interpretation. In the present case, the issue was the closing two phrases. In the original Greek, that's καὶ μὴ εἰσενέγκῃς ἡμᾶς εἰς πειρασμόν, ἀλλὰ ῥῦσαι ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ τοῦ πονηροῦ; in Latin, ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo; in the King-James translation that English-speaking Catholics still insist on using, it's "lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil." Given that today's Gospel was Jesus' temptation by Satan in the desert, I thought I'd bring my internal discussion out into the open.It was the Holy Spirit who had led Jesus into the desert to fast and pray as preparation for his ministry. Being stuck out in the desert has a way of bringing things "right down to the real nitty-gritty," as the 60s pop-song refrain went. The ancient, newly liberated Hebrews wandering in the Sinai desert were sure brought there. As eremitic tradition indicates, it can bring one face to face with demons, both figuratively and literally. And sure enough, Satan challenged Jesus face to face at the end of the fast. Thus, as I observed last year around this time, by leading Jesus into the desert "God did to the Son of God what the Son of God instructs us," in the last two phrases of the Lord's Prayer, "to ask God not to do to us." Despite knowing all about the usual historical-critical exegesis on this point, I remain puzzled by that. I know we are confidently assured that the phrases in question, at least as understood by their original audience, were eschatological in significance. Jesus was telling his followers to pray that they be spared the supreme "time of testing" that Satan would be permitted to visit upon the elect in the very last days leading up to the Second Coming. And I do not doubt that that is at least how the phrases were meant and understood. But there's very little in the words and actions of Jesus that mean only what was first explicitly stated and understood. This is no exception.

For each of us can face our own, individual eschatological crisis. Many people do: some, at the very hour of death; others, at points in their lives where a momentous, life-defining choice between real good and merely apparent good—i.e., evil—must be made. They face a test, a "temptation" in the sense of "trial." That's the kind of thing the Lord's Prayer points to, beyond the historically well-attested. I myself once faced a test like that. Of course I flunked. It is only by the infinite mercy of God that I am still a candidate for final salvation at all, and I've been doing my penance since—even though my awareness of that fact is far too recent. All of that helps me understand more deeply what the last two petitions of the Lord's Prayer mean even to those of us who consider it highly unlikely that we'll be around for the Really Big Test just before the Lord comes again.

My experience convinces me, beyond any reasonable doubt, that we do well to pray not to be "led into" any eschatological crisis. Even those of us who've been given all we need to pass the test can, and readily do, flunk. And if we flunk at the hour of death, we won't get to take a makeup exam. We do well indeed to pray that we be not led into that "temptation." But the likelihood of finding ourselves in the thick of it rises with our presumption and sloth. That is why we are exhorted to "watch and pray," knowing full well we are sinners and ever seeking to become more like the one for whom we are watching, through whom all our prayers reach the Father.

Since Jesus was incapable of sin, he was sure to resist his "temptation" by Satan in the desert. Since we are sinners, he urges us to pray not be led into such temptation; yet his victory over Satan, culminating on the Cross, simultaneously shows us the pattern we must emulate if we are to reverse the effects of original sin in our lives, and gives us the power to do so. By refusing to turn stones into bread when he was famished, Jesus showed us that we must put fidelity to our mission as disciples above our personal needs and desires. By refusing to gain temporal power at the price of worshiping Satan, Jesus showed us that real power, the only kind that matters, consists in submission to God. That's what Adam and Eve forgot. By refusing to throw himself off the temple parapet in the expectation that he would be saved by angels, Jesus let God be sovereign rather than at his beck-and-call. And after all that, he was of course ministered to by angels.

Thus he gave us the power and the promise. Let us not forget that they are the fruit of a struggle that our first parents lost and that we often lose. It is by doing what we must but cannot do for ourselves that Jesus gave us our chance to do it at all. Thank God it's never by ourselves, like him in the desert. We always have him, and his spotless Mother, to rely on.

Sunday, February 03, 2008

The attitude of beatitude

Welcome back, dear readers. After Christmas I worked sick and tired for weeks, both at my main, paid job and at the unpaid job of looking for a better job. But I've never been sick and tired of this blog. Quite the contrary, given the generosity you showed me during Advent, I've felt guilty for neglecting what is currently my ministry and a bit too ashamed to admit it. Which brings me to today's topic.

Welcome back, dear readers. After Christmas I worked sick and tired for weeks, both at my main, paid job and at the unpaid job of looking for a better job. But I've never been sick and tired of this blog. Quite the contrary, given the generosity you showed me during Advent, I've felt guilty for neglecting what is currently my ministry and a bit too ashamed to admit it. Which brings me to today's topic.The Gospel reading for the ordinary form of the Roman Rite was Matthew's version of the Beatitudes. The homilist at Belmont Abbey today, Fr. Christopher Kirchgessner, sounded a theme that anybody who's ever been afflicted with "Catholic guilt" can duly appreciate. "In all honesty," he said, "it is impossible for us" to live out the Beatitudes consistently, or even most of the time. Everybody knows that deep down, but it must be said anyhow because not all Christians are willing to admit it. Many Catholics still seem to believe, even if they don't say out loud, that admitting as much would be tantamount to giving people license to sin. Since that would be unacceptable, they embrace moralism as the way to forestall antinomianism. To be sure, they know that moralism is not enough either. They retain enough spiritual wisdom, indeed orthodoxy, to profess that divine grace is also necessary. Thus they suppose that something called "sanctifying grace," thought of as a kind of divine fuel always on tap at the sacraments, ready to be pumped into the soul, is there to propel us reliably toward the goal of becoming "good enough" to merit heaven. We can check our progress by honestly admitting how many "mortal sins" we commit, how many vices we retain, and by measuring just how mortal and how vicious those things are. Our degree of holiness varies inversely with the product of the relevant quantities of evil. On this picture, the best hope for most of us is to squeak into purgatory if we and others pray and work hard enough to have kept the level of evil below a certain threshold when we die.

Such is the operative spirituality that produces "Catholic guilt." The thing is very much with us, even in the writings of otherwise sound theologians. In an article with whose main thesis I heartily agree, for example, Cardinal Avery Dulles remarks: "Catholics can be saved if they believe the Word of God as taught by the Church and if they obey the commandments." Hmmm. This is from a man who is not only a prince of the Church but a theologian very much involved in the Lutheran-Catholic dialogue that produced the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification. Now I'm sure there is a way to interpret said remark so that it comes out consistent with the Gospel. I don't think it would be right to accuse a man like Dulles, to whose work I owe much, of heresy. But what is the ordinary Catholic, be they lay or clerical, likely to hear in such a remark, which sums up the import of too much Catholic preaching and catechesis even today, even in "progressive" circles that focus on social sin rather than personal sin? They are likely to hear that we're supposed to be, or become, "good enough" to get into heaven and have been given all we need for just that. That's what they've heard all their lives, even when it was not exactly what their teachers meant to say. It raises Protestant hackles—and rightly so. For sooner or later we come to realize, if we're humble enough to be honest, that we will never be "good enough." People who realize that before they're equipped to deal with it often lapse from the practice of the Faith, or even from the Faith itself. It's hard to blame them for refusing to dwell in toxic guilt, especially when nobody has presented them with a healthier model of the spiritual life. Others never admit their human incapacity openly enough to avoid beating themselves up all their lives—or if they do admit the incapacity, can't permit themselves any excuse for it because every possible excuse seems hollow. Every adult, practicing Catholic knows at least one Catholic like that. I know many; for a long time, I was one of them. What is to be done?

One approach is, in effect, Martin Luther's: stop imagining that anything you can do can make you right with God. Respond to the Gospel simply by accepting God's unconditional love. When you sin, pecca fortiter; just remember to repent by throwing yourself on divine mercy, in faith alone. That is the attitude of many Protestants, especially those who today call themselves "evangelicals." It is why they not only admit they will never be "good enough" but aren't much bothered by the fact. They tend to see themselves as righteous only by imputation, in faith. Not only do they not see themselves as having "earned" salvation; they don't even see themselves as being transformed by it. Such is certainly one way, indeed a centuries-old way, to avoid scrupulosity and Catholic guilt. That's how Luther did it. And it makes a certain sort of sense. If you don't think it's either possible or desirable to seek inner transformation, to cooperate in a process of being remade in Christ and thus divinized, then you won't feel bad about failing to do so.

Yet one of the reasons I could never be Protestant is that such an attitude, though not wholly wrong, is not wholly right either. The Great Tradition of both Catholicism and Orthodoxy, from which the Reformation mostly departed to its detriment, indicates that we are made righteous not only by imputation but also by transformation. That occurs for those Christians who, having reached the age of reason, choose to cooperate with what the Scholastics called "prevenient" grace: the divine activity we need in our souls order to accept all other divine gifts. And that's because the baptismal vocation, the very goal of the Christian life, is to become "partakers of the divine nature." Divinization is not something that just gets zapped into us after we die, if we happen to have chosen to "believe" before we die. It begins with baptism and, if we would have it so, continues in the here and now. We don't deserve such a gift; we can do nothing to bestow it on ourselves; to that extent, Luther was right. But for those of us who can choose anything at all for ourselves, it doesn't bear fruit without our cooperation. To that extent, Trent was right—and was consistent with what was right in Luther.

The best way to think of the process is to compare it with a successful marriage. It is often said, rightly, that marriage is not a 50-50 but a 100-100 proposition. Couples in which both parties put their all into the marriage are sanctified by their marriages. The same goes for the roles of divine grace and human will in the ongoing process of salvation. The work of salvation is wholly God's; but it is also wholly ours, to the extent we let ourselves be empowered to contribute to it. Given that Christ is the Bridegroom of the Church, which is us, that could hardly be otherwise. To the extent we recognize and accept that, we will be enabled to have the attitude of beatitude. That doesn't mean we will always give our all or that the process will ever be complete in this life. Even the saints are wretched sinners. It means that God always gives us the chance, and the power, to resume going in the right direction. His mercy is what takes us the rest of the way.

Sunday, January 13, 2008

Theophany and vocation

For the benefit of the few readers who don't already know, I note that today's feast in the Roman calendar, the Baptism of the Lord, is really the same feast that the Orthodox celebrate as the Holy Theophany or "Epiphany." When I first learned of that correlation in college, I at once associated the idea of theophany with that of vocation and that of baptism with both. Apparently, that helped fool some progs into thinking I might be one of them. For back in the 1970s, Roman Catholics were still trying to wrap their minds around the idea that baptism was something more than the spiritual equivalent of mandatory neonatal therapy: the "washing away the stain of original sin" the Church did for babies lest they die and get stuck in limbo before we got round to doing right by them. Vatican II had quite explicitly recovered the richer, ancient understanding of the "baptismal vocation," of course; but the idea that people other than priests or vowed religious had vocations seemed, and in many quarters still seems, a rather newfangled idea among Catholics.

For the benefit of the few readers who don't already know, I note that today's feast in the Roman calendar, the Baptism of the Lord, is really the same feast that the Orthodox celebrate as the Holy Theophany or "Epiphany." When I first learned of that correlation in college, I at once associated the idea of theophany with that of vocation and that of baptism with both. Apparently, that helped fool some progs into thinking I might be one of them. For back in the 1970s, Roman Catholics were still trying to wrap their minds around the idea that baptism was something more than the spiritual equivalent of mandatory neonatal therapy: the "washing away the stain of original sin" the Church did for babies lest they die and get stuck in limbo before we got round to doing right by them. Vatican II had quite explicitly recovered the richer, ancient understanding of the "baptismal vocation," of course; but the idea that people other than priests or vowed religious had vocations seemed, and in many quarters still seems, a rather newfangled idea among Catholics.Still, it is no coincidence that the only place in the Gospels where all three persons of the Trinity are presented as manifesting themselves perceptibly and together is Jesus' ritual baptism by his cousin John. The occasion was the inauguration of Jesus' public ministry: the end of his time of preparation and the beginning of his actual mission. Just as it was the baptism he would undergo in his humiliating Passion that would give all baptism its power, so the humility he showed by letting his divine Person be baptized, when he himself did not need it, was the beginning of that passion. That the power of sacramental baptism ex opere operato, by which we are initiated into the Mystical Body of Christ, the Church, is our ontic incorporation into the divine life, is manifest in the theophany of the Trinity at Jesus' own baptism. When baptized into Christ, each Christian becomes the Father's pure and beloved child, filled with the Holy Spirit to carry out in this world a mission special to them.

Many people have little or no idea what that mission is. That is partly because most of us who have not undergone a well-conducted RCIA grasp only dimly, at best and if ever, what baptism itself makes us into and calls us to. Whether our day-to-day environment is secular—as in most cases—or religious, the lingering effects of original sin seem a lot more real to cradle Catholics than our divinization; and so it seems even to converts once the initial glow wears off. It has long been so. Once the Roman world became nominally Christian, so that being baptized became the cultural norm, it was inevitable. Most Catholics even today were baptized as infants and therefore remember nothing of the event. For them, there's no there there. Consequently, and absent a kind of spiritual progress that is all too rare, being Catholic can seem more a burden than a blessing: either a set of cultural and psychic baggage one can't quite shake, or another compartment of life with its own ceaseless demands and challenges, ones that must somehow be balanced with all the others in all the other compartments. It does not occur to most Catholics that the most beautiful and important thing about each of them, as individuals, is a pure divine gift: their being re-fashioned, in baptism and on through to the grave, in the image of Christ. For they are each members of his Mystical Body, whose purpose is to bring her Head, God's only-begotten Son, into the world even as each is formed for life eternal. Most of us are much more concerned with measurable performance, especially in tasks the world sets us and approves. The minority who consistently succeed at all that are often among the least likely to understand what their most important task really is.

And so today, with full knowledge of my failures in love and work, I am grateful to God and hopeful for the future. God has allowed me to retain no illusions about my worthiness or success; but neither am I exempt for a moment from obeying his commandments and using my gifts to the full. The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, each the same God as the others, do not exempt me because, calling me to become one of the "partakers of the divine nature" (2 Peter 1:4), the Trinity offers me the power to do those things. That power is the life of the Trinity itself, drawing me into itself, beyond this world but very much in it. My prayer today is that I never lose sight of that, and that I always act accordingly. That is my prayer for each of us.

Sunday, December 30, 2007

The Feast of the Holy Family

When Herod had died, behold, the angel of the Lord appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt and said, “Rise, take the child and his mother and go to the land of Israel, for those who sought the child’s life are dead.”

He rose, took the child and his mother, and went to the land of Israel. But when he heard that Archelaus was ruling over Judea in place of his father Herod, he was afraid to go back there. And because he had been warned in a dream, he departed for the region of Galilee.

That great practitioner of the spiritual via moderna, Johann Tauler, observed by means of commentary:

Herod, the one who pursued the child and wanted to kill him, represents the world which clearly kills off the child, the world that we must by all means flee if we want to save the child. Yet no sooner have we fled the world exteriorly… than Archelaus rises up and reigns: there is still a world within you, a world over which you will not triumph without a great deal of effort and by God’s help.

For there are three strong and bitter enemies that you have to overcome in you and it is with difficulty that we ever win the victory. You will be attacked by spiritual pride: you would like to be seen, taken note of, listened to… The second enemy is your own flesh, assailing you through bodily and spiritual impurity… The third enemy is the one that attacks by arousing malice in you, bitter thoughts, suspiciousness, ill will, hatred and the desire for revenge… Would you become ever more dear to God? You must completely forsake all such behaviour, for all this is the wicked Archelaus in person. Fear and be on your guard; he wants to kill the child indeed…

Yep, there's that "inner Archelaus" I'm so in touch with. I can say that I've "fled the world," if by flight from the world is meant refusing to let one's exterior course of life be motivated by those idolatrous lusts which so clearly motivate "the world." Those are unashamedly on display in the media: in the news of politics, in the pornography developed to sell things, in entertainment, and especially in those forms of entertainment which pass for news. All that glorification and pursuit of money, sex, power, fame, or some combination thereof is about trying to become as god by glutting rather than emptying oneself. It's always at others' expense, especially that of the most vulnerable; and it's all vainglory. Yet it would be absurd to take pride in fleeing all that exteriorly; flight is only the beginning, not the end, of one's itinerarium in mentis Christi. The hard work commences within. The interior enemies whom Tauler knows and names are those whom I fight daily in my spiritual combat. They are closer to me than my best human friends: I see their leering faces all the time. When they gain ground on me, thanks to my own sloth and pusillanimity, I lose touch with "the child"—my true "inner child"—and so cannot show Him to others. Perhaps there is some connection between that and where I stand in relation to my own children. The outer life cannot be righted until the inner life is.

Of course the Holy Family is not about me to any greater extent than it's about anybody else. It's about you too. But I try to be honest about myself, publicly, so as to encourage you to be that with yourself, privately and today. If you take up the invitation with the Spirit's help, you will be able to see your way to Galilee a bit better. Perhaps you can then be more a help than a hindrance to making your own family—whatever form family may have in your life—a bit more like the Holy Family. At least that is my prayer for today, for me and for each of us in that family of God known as the Church.

Sunday, December 23, 2007

The names of Christ

Something about today's set of Bible readings, for the Fourth Sunday of Advent in the normative Roman calendar, first puzzled me when I was twelve. Not that I got far raising the issue with the nun who taught me that year: she saw my theological questions mostly as clever attempts to avoid the disciplines I really needed, such as those of penmanship, punctuality, and personal appearance. That factoid well prophesied the course of much of my later spiritual life. Even so, I suspect others have been similarly puzzled, though I've never met anybody who let on that they were, and since then I've never formally researched the issue. Herein I shall approach it fresh from the recent debate in these quarters about "the plain sense" of Scripture.

Something about today's set of Bible readings, for the Fourth Sunday of Advent in the normative Roman calendar, first puzzled me when I was twelve. Not that I got far raising the issue with the nun who taught me that year: she saw my theological questions mostly as clever attempts to avoid the disciplines I really needed, such as those of penmanship, punctuality, and personal appearance. That factoid well prophesied the course of much of my later spiritual life. Even so, I suspect others have been similarly puzzled, though I've never met anybody who let on that they were, and since then I've never formally researched the issue. Herein I shall approach it fresh from the recent debate in these quarters about "the plain sense" of Scripture.We know that 'Christ' is not Jesus' surname, any more than 'H' is his middle initial. 'Christ' is Anglicized Greek for a Hebrew term meaning 'anointed one', which in turn is usually transliterated as 'Messiah'. It is a title, not a name of the kind given by parents to their children at birth or thereabouts. But what of 'Emmanuel', a name we seem to hear about only during this season? It is not an ordinary given name and has not taken root, like 'Christ', as a title; yet according to Matthew, alluding to Isaiah 7:14, "they shall name him Emmanuel, which means 'God is with us'." Well, who is this "they"? As far as I can see across time as well as space, "they" are mostly carol-singers. Now for all I know, this or that sector of Eastern Christianity might have a tradition of calling Jesus 'Emmanuel'; if so, that would certainly answer the question. But in the last analysis, I doubt it matters much who "they" are so long as there's somebody taking a cue from the infancy narratives in the New Testament. What matters instead are two other things.

First, the interrelation of meaning between the names 'Jesus' and 'Emmanuel' is theologically significant. 'Jesus' means 'he who saves', specifically from our sins. Given that the two names 'Jesus' and 'Emmanuel' are somehow names for the same person, the significant point is that the one who "saves" us from our sins is the one who is "with us." Conceptually, that equivalence is not at all obvious. God has not saved us from our sins by decree: remotely, impalpably, and at some time in the past. Many nominal Christians carry on as though he did; but if he did, we could only acknowledge the fact in the abstract and wonder how it has do with our actual lives. In Jesus Christ, God become a man, God saves us from our sins by having pitched his tent among us with the Incarnation, by having suffered with us on the Cross, and by continuing to suffer precisely in us, as he extends the presence of his risen Body into the world through the Church. God thus saves precisely by being with us. For me, that was a breakthrough insight about the Atonement. The well-known juridical metaphor for salvation, by which Jesus' death saved us by paying an infinitely great debt to an infinite creditor, is destructive when taken too literally. What Jesus really did, and does, is invite us to re-integrate into divinity by being intimately present to us in every moment of life—no matter how small or large, no matter how nasty or glorious—and soliciting our 'yes'. If and when forthcoming, that response is punctualized and fortified in the sacraments, above all in the Eucharist.

The other point which matters is that biblical literalism is dangerous. In the past I've made much of the fact that Matthew's use of Isaiah 7:14's reference to "a virgin"(Septuagint: parthenos) is not warranted as a strict deduction from the original Hebrew text but only as an inspired abduction. You can't get from there to here by being merely literal. Similarly, 'they shall call him Emmanuel' is not true if taken as a prediction about what Jesus would be normally called by name, or even by title. Its truth consists in its being a proleptic summation of what Jesus is for us. It is the Gospel-in-germ. That of course is not the "plain sense" of the term for the ignorant and the literal-minded. But it is the plain sense for those who read today's gospel in the context of Tradition and the teaching authority of the Church.

Sunday, December 09, 2007

Elemental powers

Today during Vespers at Belmont Abbey, one of the readings I heard was from St. Paul's Letter to the Colossians. He asks: "If you died with Christ to the elemental powers of the world, why do you submit to regulations as if you were still living in the world?" (Col 2:20). As the Pope's new encyclical Spe Salvi shows us,

Today during Vespers at Belmont Abbey, one of the readings I heard was from St. Paul's Letter to the Colossians. He asks: "If you died with Christ to the elemental powers of the world, why do you submit to regulations as if you were still living in the world?" (Col 2:20). As the Pope's new encyclical Spe Salvi shows us,that question remains quite pertinent today.

In context, of course, Paul was upbraiding the Colossian Christians for their tendency to observe pagan rituals as though the original religious myths motivating such things were legitimate. They didn't quite "get" that Christ had liberated them from all that. But if the pagan gods were and are false, then just what were these "elemental powers" to which the baptized had supposedly died with their incorporation into Christ? And I mean the real ones, whatever they were—not the gods of mere imagination, if that's what some of "the gods" were. Given the gravity of the issue, the answer has to be perennial, not just local, and therefore one of contemporary relevance.

One part of the answer is clear enough: fallen angels, or "devils." Jesus talked a lot about those, especially about their chief, who was his chief adversary. It is to such as those that Paul, in the same passage from Colossians, referred when he said of Christ that "despoiling the principalities and the powers, he made a public spectacle of them, leading them away in triumph by [the Cross]" (Col 2:15). That there are such beings is the experience of the saints, of the possessed, and therefore of true exorcists, as well as the irreformable teaching of the Church. But devils are not the whole story; and for good reason, it's not the part the Pope speaks of in SS. Today, the most obvious referent of the term 'elemental powers' is to the blind forces of Nature itself, most specifically to what is now called "evolution." Yet that referent too has its roots in the ancient world of which Paul spoke. The continuity is instructive.

Until a century or two before Christ, little or no distinction had generally been made between unseen personal beings, among whom were devils, and what we would now call "the laws of nature." Skeptical philosophers aside, the masses of people seemed to believe that the seasons unfolded, the stars stayed in their courses, the sun rose and set, and so on, because there were living spirits, "gods," making sure that such things kept happening. That is why the earliest known Western philosopher, Thales, had said: "All things are full of gods." Some of those "gods" were accounted good, others not so good, and some oscillated between the two. So when one paid obeisance to "the gods," one was merely trying to stay on the good side of the unseen personal powers of the universe. There was no hope of escaping their power: the best one could do was limit one's exposure to their caprice, or at least avoid exciting their malice. Such led to a certain fatalism among the ancient pagans, even the Romans. And such fatalism persisted as the skeptical rationalism of the philosophers began to affect the general sensibility. Whether "the gods" literally existed or not, most people saw little or no hope of getting beyond the world, even those who believed there was some sort of afterlife. Their horizons were limited to this world, or to what was taken to be this world. That is why Paul also says to the Ephesians that, before their encounter with Christ, they were "without hope and without God in the world" (Eph 2:12). The Pope puts it thus:

Myth had lost its credibility; the Roman State religion had become fossilized into simple ceremony which was scrupulously carried out, but by then it was merely “political religion”. Philosophical rationalism had confined the gods within the realm of unreality. The Divine was seen in various ways in cosmic forces, but a God to whom one could pray did not exist. Paul illustrates the essential problem of the religion of that time quite accurately when he contrasts life “according to Christ” with life under the dominion of the “elemental spirits of the universe” (Col 2:8).

That's what St. Paul indicated Christ had freed believers from. And so it was. But today in the "developed" world, we live in a public reality that is largely post-Christian, even as in some less developed corners of the world people still live under the spiritual thralldom of an essentially pre-Christian paganism. The philosophy of secular materialism, which can take either agnostic or atheistic forms, is the new fatalism. As such, it is ultimately a counsel of despair. And it is to just that despair that the Christian message addresses itself as much now as it did then, when greed, lust for power, and sexual perversions were as open as they are now. Once again, SS (footnotes omitted):

In this regard a text by Saint Gregory Nazianzen is enlightening. He says that at the very moment when the Magi, guided by the star, adored Christ the new king, astrology came to an end, because the stars were now moving in the orbit determined by Christ. This scene, in fact, overturns the world-view of that time, which in a different way has become fashionable once again today. It is not the elemental spirits of the universe, the laws of matter, which ultimately govern the world and mankind, but a personal God governs the stars, that is, the universe; it is not the laws of matter and of evolution that have the final say, but reason, will, love—a Person. And if we know this Person and he knows us, then truly the inexorable power of material elements no longer has the last word; we are not slaves of the universe and of its laws, we are free. In ancient times, honest enquiring minds were aware of this. Heaven is not empty. Life is not a simple product of laws and the randomness of matter, but within everything and at the same time above everything, there is a personal will, there is a Spirit who in Jesus has revealed himself as Love.

The contrast now is as stark as it was back then. Intellectually the counsel of despair might seem more persuasive, because we know so much more about how the universe in general and life on earth in particular have developed. But existentially, the choice remains exactly the same now as it was when the Church was new: despair, or hope.

Sunday, November 25, 2007

Christ the King, freedom, and divorce

For today's feast, Fr. Philip Powell, OP, preaches:

For today's feast, Fr. Philip Powell, OP, preaches:Paul reminds us and we cannot forget: “…in him were created all things in heaven and on earth, the visible and the invisible…all things were created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.” Christ the Crucified rules from his cross because in him “all the fullness was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile all things for him…” Christ for us is everything. There can for us be no appeal to economic efficiency, political expediency, popular demand, or incremental progress. Christ rules by transforming cold hearts, by turning hard heads, by overthrowing obstinate wills; he rules in virtue, in strength, by being for us weak in condemnation and mighty in compassion. And we, as his body, his members can be nothing less, nothing weaker. We are subjects of a Crucified King.

I want to offer a meditation on how American Christians of all churches need to see that in relation to what is thought of as "freedom"—especially with regard to the basis of the family, which in turn is the basis of civil society.

Let's start with a set of facts that are becoming increasingly difficult to deny or even hide from: what Dr. Jennifer Roback Morse calls, in the current issue of the National Catholic Register, "the perverse incentives" of our family-law system. As I argued last July 4, the way such matters as divorce, custody, domestic violence, and child support are being handled in this country signifies a steady erosion of personal freedom in the name of a legal regime that was originally supposed to enhance personal freedom. Taking her cue from Dr. Stephen Baskerville's hard-hitting, well-argued book Taken into Custody: The War Against Fatherhood, Marriage, and the Family, she writes:

First, no-fault divorce frequently means unilateral divorce: One party wants a divorce against the wishes of the other, who wants to stay married. This fact means that the divorce has to be enforced. The coercive machinery of the state is wheeled into action to separate the reluctantly divorced party from the joint assets of the marriage, typically the home and the children. Involving the family court in the minutiae of family life amounts to an unprecedented blurring of the boundaries between public and private life. People under the jurisdiction of the family courts can have virtually all of their private lives subject to its scrutiny. If the courts are influenced by feminist ideology, that ideology can extend its reach into every bedroom and kitchen in America. Thus, the social experiment of no-fault divorce, which was supposed to increase personal liberty has had the unintended consequence of empowering the state.

That has happened to millions of people; men especially are subject to such coercion. Most of us hate it. What I didn't realize, however, is that the people who most directly exercise the authority in this system hate it too. Roback Morse continues (emphasis added):

I had an unusual opportunity to see this first-hand last summer when I did a Continuing Legal Education workshop for judges. Most of the judges had significant experience with family courts, so they were unusually well-informed. My audiences are usually amazed when I point out that family courts perpetrate greater invasions of personal privacy than any other governmental agency. Not the judges. I had expected some resistance from them on this point. After all, they are the ones doing the intruding.

When I ran through my usual litany of courts telling fathers how much money they have to spend, how little time they get to spend with their kids and who gets to spend Christmas Day with the kids, the judges were all shaking their heads. I asked: “So, do you enjoy that part of your jobs?” The audible moaning said it all: They hate that part of their jobs.

Audiences are sometimes surprised to learn that women initiate most divorces. They are even more surprised when I tell them that women aren’t necessarily worse off economically after divorce. After all, “the most quoted demographic statistic of the 1980s” was the claim that women’s standard of living falls by 73% after divorce, while men’s rises by 42%.

I usually have to take some time to refute that claim. But the judges already knew that. They all started shaking their heads when I flashed those statistics on the screen for the purpose of refuting them. One of the judges got exasperated. He stood up and said, with obvious disgust in his voice, “These women want me to throw their husbands out of the house, make him pay child support, while she keeps the kids to raise herself without interference from him.”

General nods of agreement all around the room. No fathers’ rights advocate could have said it better.

And it's not just the judges:The court-appointed therapists, the domestic violence experts, the visitation supervisors, the teachers of parenting classes, all these experts seem to be there to help divorcing families. But on Baskerville’s telling, they simply extract additional payments from the family, and do nothing to save the marriage. He reports that even mediators find that they are not allowed to try to preserve the marriage. Their role is simply to talk the reluctant party into acquiescing. Baskerville represents all these professionals, including the lawyers and judges, as having a self-interested motive in stoking the flames of personal resentments and maintaining the divorce industry...

I have also talked to many family law attorneys who are fed up with narcissistic and myopic clients. How can it be that all these people are keeping the system going out of their own self-interest, and yet profess disdain for that same system?

I think the answer lies in what economists call perverse incentives.

No one likes the actual outcome of the system, but no one has an incentive or the ability to change it. So people go along, following the rules as laid down, trying to make marginal improvements to the best of their ability, and still being sickened by the whole sight. The incentives are so perverse that it is as if everyone were motivated by a desire to create as many divorces as possible.

So that's what it's come to in this country: in the name of freedom, justice, and "the best interests of the children," we are destroying the basic unit of civil society by means that hardly anybody likes yet most everybody feels helpless to change. We are all becoming prisoners of evil. What better evidence can there be that the wrong king is ruling our hearts? Make no mistake: if we continue on our present path, our society is doomed.

In the long run, the only alternative is to let the right King rule in our hearts. Marriages need to be saved, not destroyed. The incentives—legal, financial, therapeutic, religious—need to reflect that. But what's needed can only occur if all involved emulate the Crucified King. That cannot be begin with legislation and coercion: it must begin with conversion of hearts, one at a time; only if that happens on a large scale can the legal system be changed to reflect it. Only then can true freedom survive. This feast of Christ the King, that is what I pray for. I offer my prayer for all those, including myself, who have been part of the problem.

Monday, November 19, 2007

Ratzinger, Scripture and the development of doctrine